Magdalen in the 1870s was a far smaller college than today; when Wilde arrived, there were only about 100 students, all male. Oxford’s streets were still cobbled, and lit by gas-lamps; the city’s suburbs, such as North Oxford and the Iffley Road, were relatively undeveloped. Wilde’s fellow undergraduates wore college caps and gowns for much of the day, and chapel attendance was compulsory.

Thanks to his brilliant performance in the admissions exams, Wilde was elected to a “Demyship”; a form of scholarship which Magdalen still offers to second-year students today. Wilde was conspicuous for his slight Irish accent, long hair, and the brilliance of his speech. On Sunday evenings, he entertained friends with “brimming bowls of gin-and-whisky punch; and long churchwarden pipes, with a brand of choice tobacco”.

Most of Wilde’s Magdalen friends became lawyers or clergymen. Chief among them was William Welsford Ward, a fellow Classicist from Bristol, who, writing decades later, remembered “the charm of [Wilde’s] companionship and conversation […]How brilliant and radiant he could be! How playful and charming!”. Magdalen had a reputation for being an especially sociable college, and had – then, as now – a very active JCR (Junior Common Room).

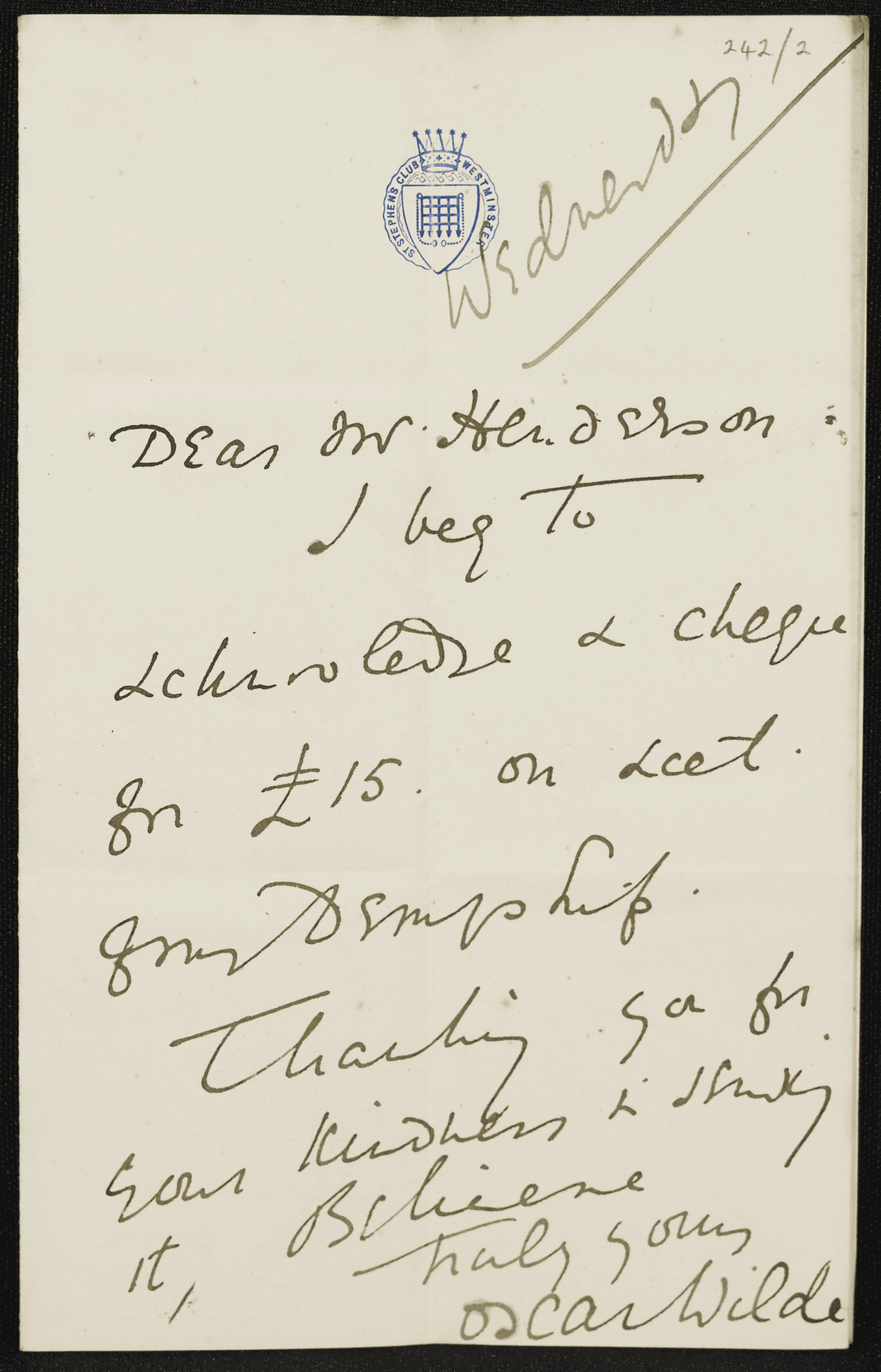

Receipt Signed by Oscar Wilde for his Demyship (1879)

Wilde received his “demyship”, a form of scholarship unique to Magdalen, between 1874–9. His parents also paid him a substantial allowance. While at Magdalen, he spent freely – at his tailor’s, “Muir”, his jeweller, “Osmond”, and an Oxford department store, “Spiers’ Emporium”.

Magdalen College Archives, EP/242/2

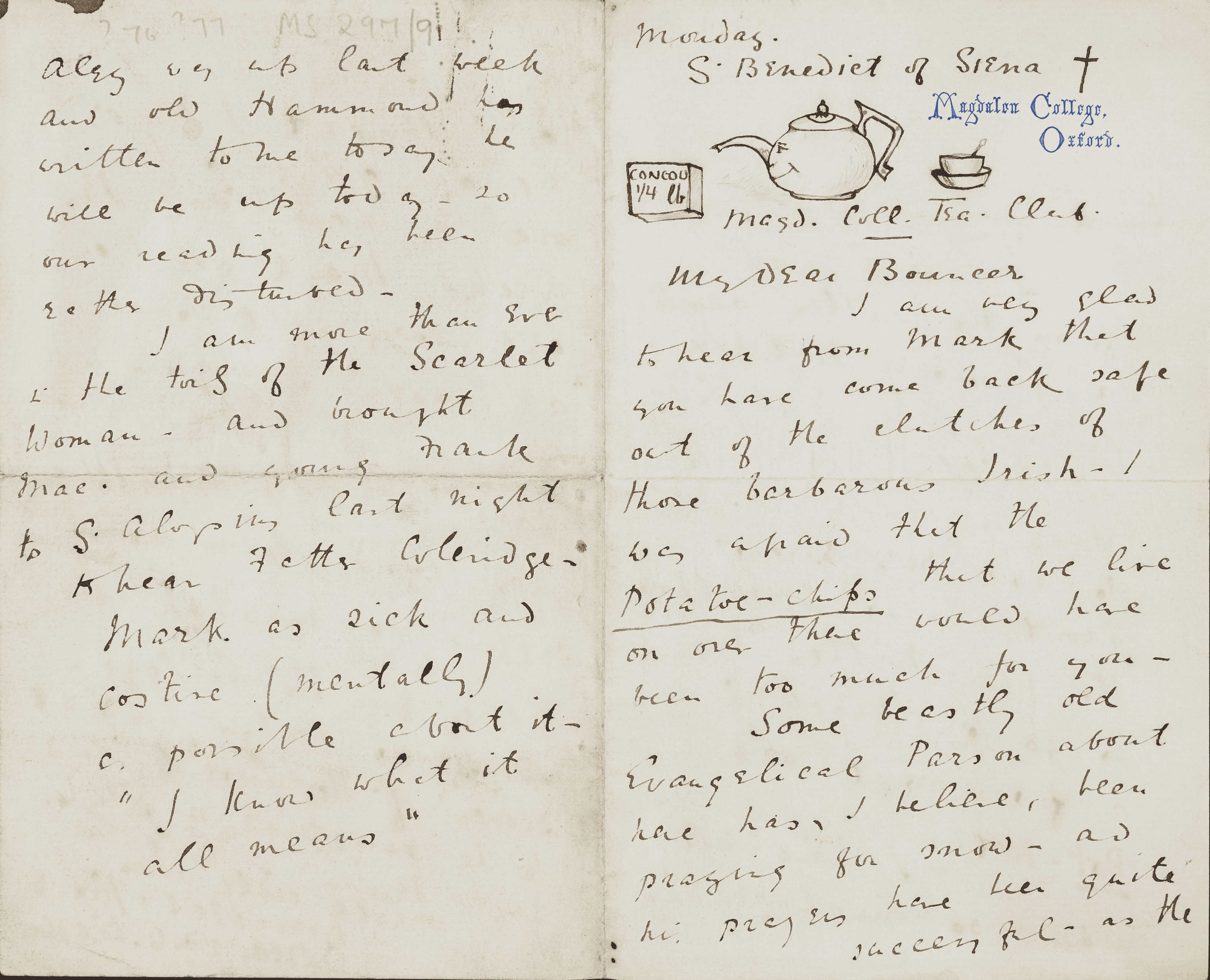

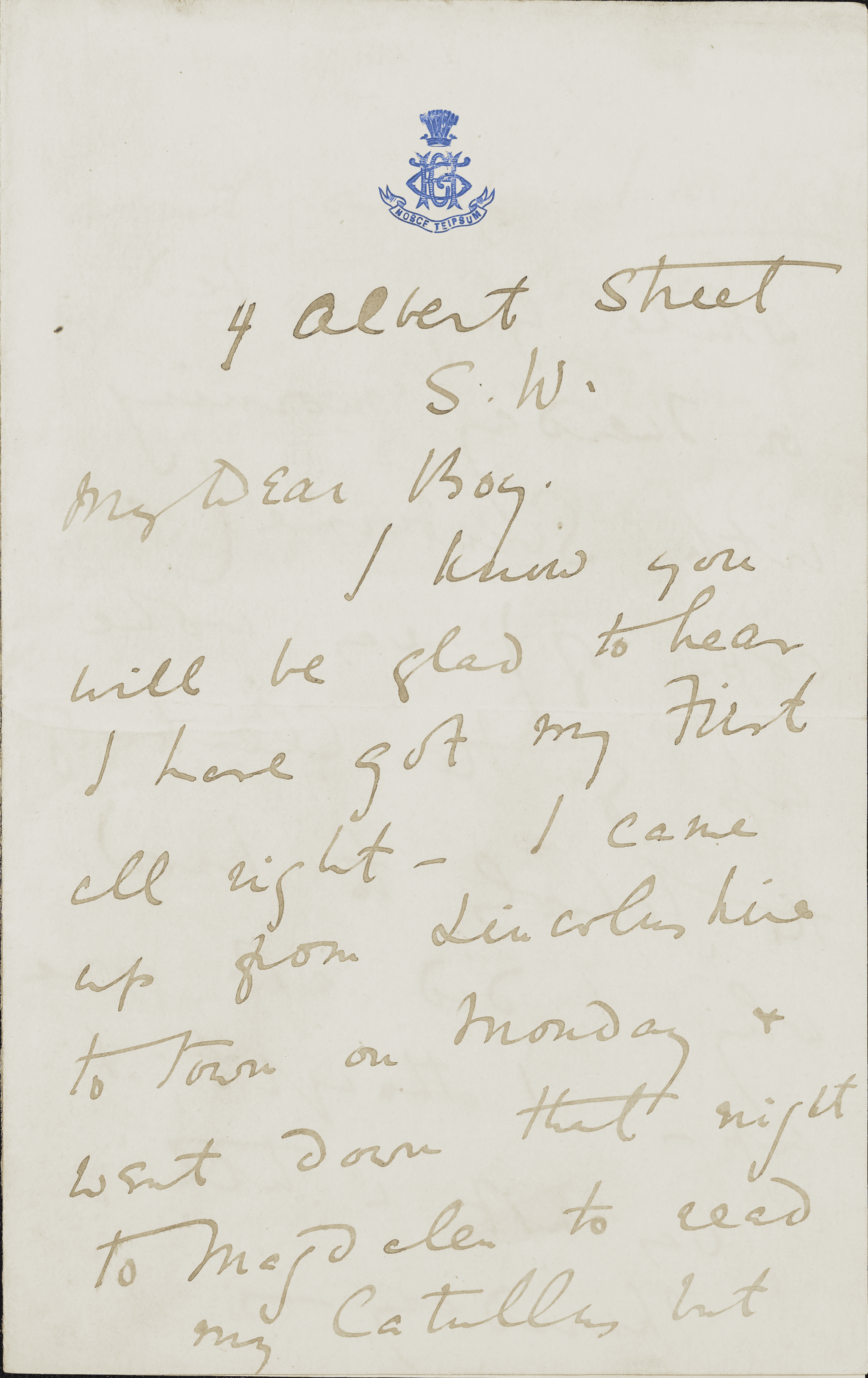

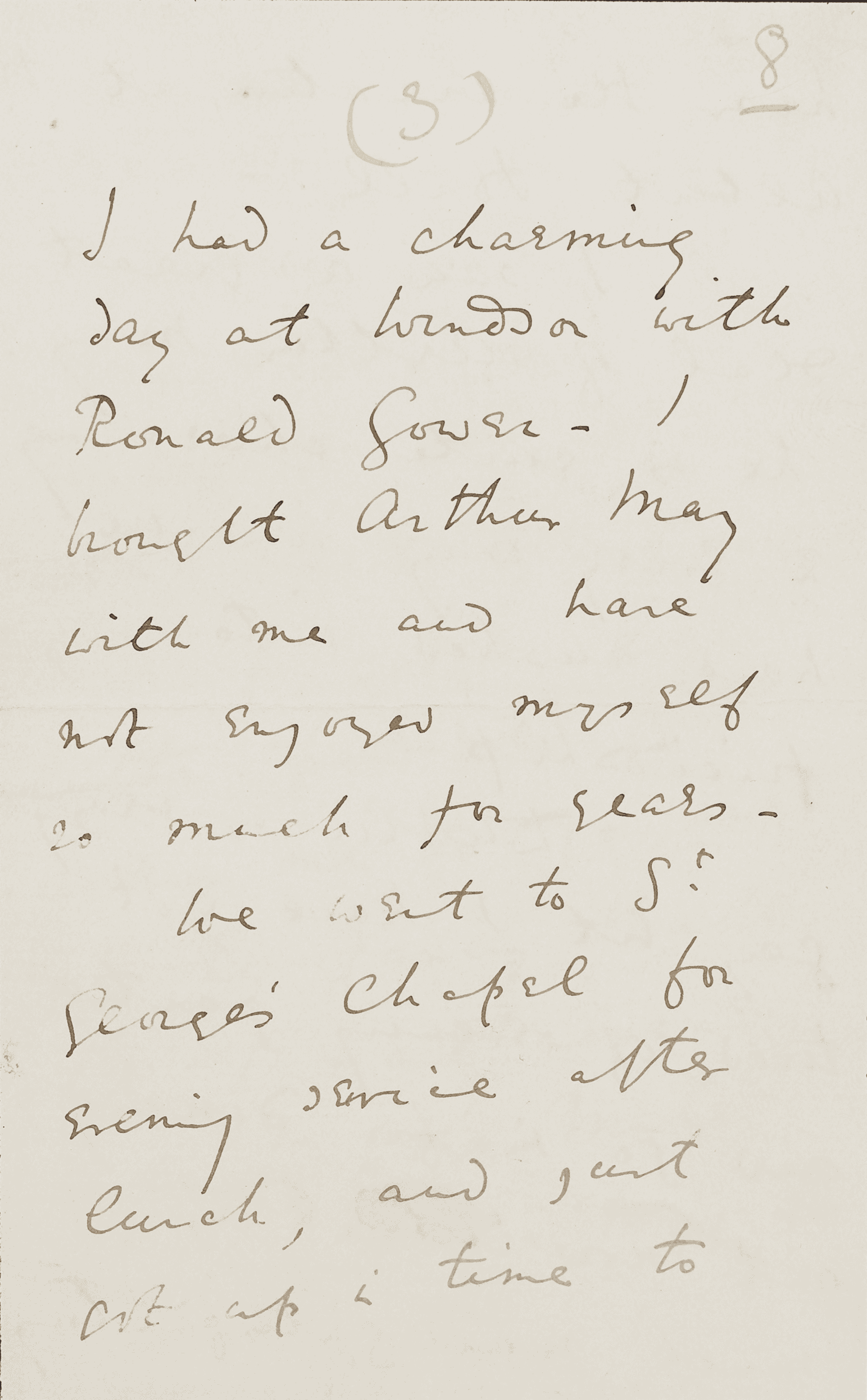

Letter from Wilde to William Ward (20 March 1876)

William Welsford Ward (1854–1932) was Wilde’s best friend at Magdalen. Born in Bristol, Ward read Greats, two years above Wilde, and was President of Magdalen JCR. Wilde has doodled a highly Aesthetic teapot at the top of his letter to Ward.

Magdalen College Archives, MS 297/9

The gift of Miss Cecil Ward

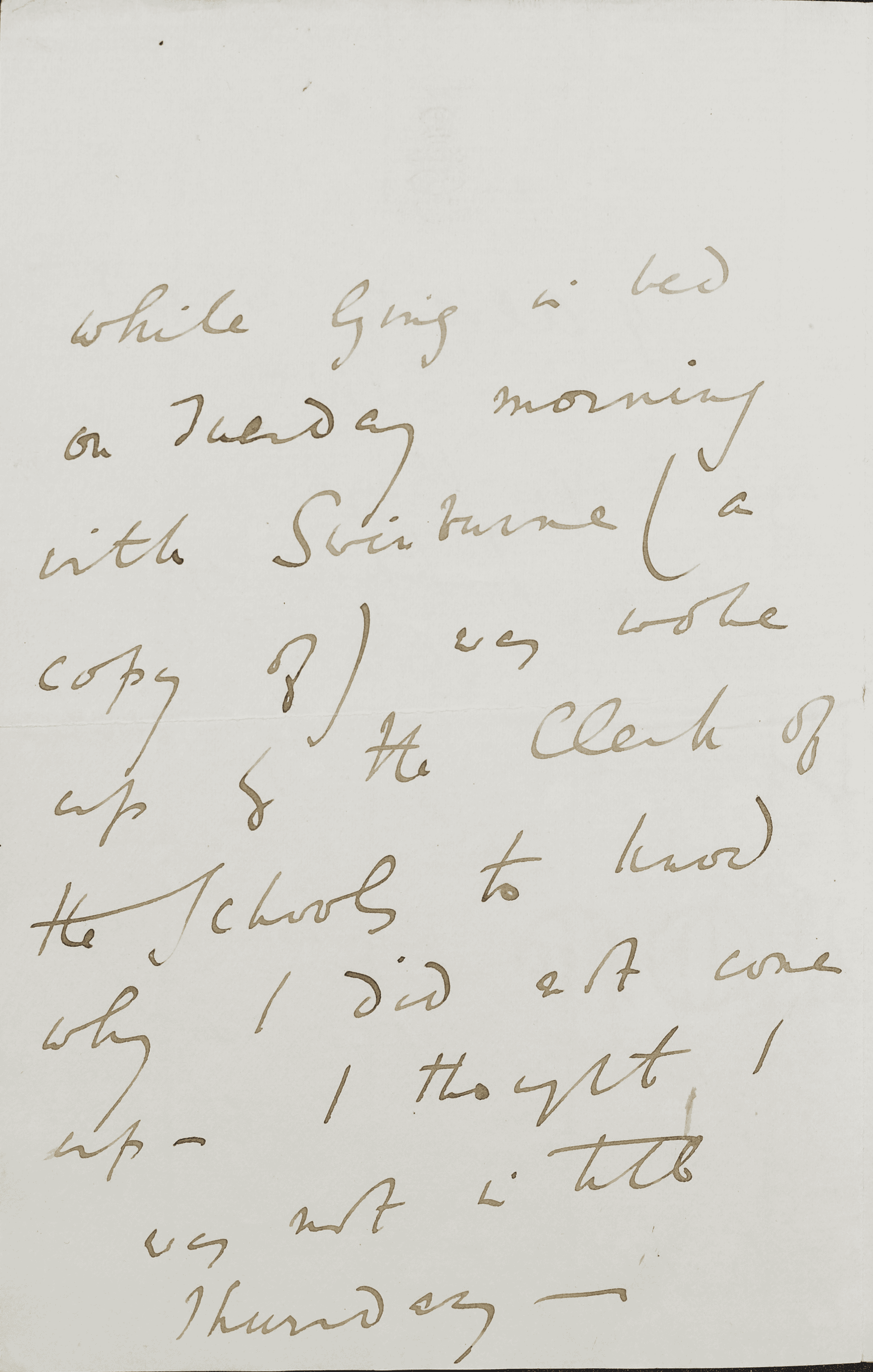

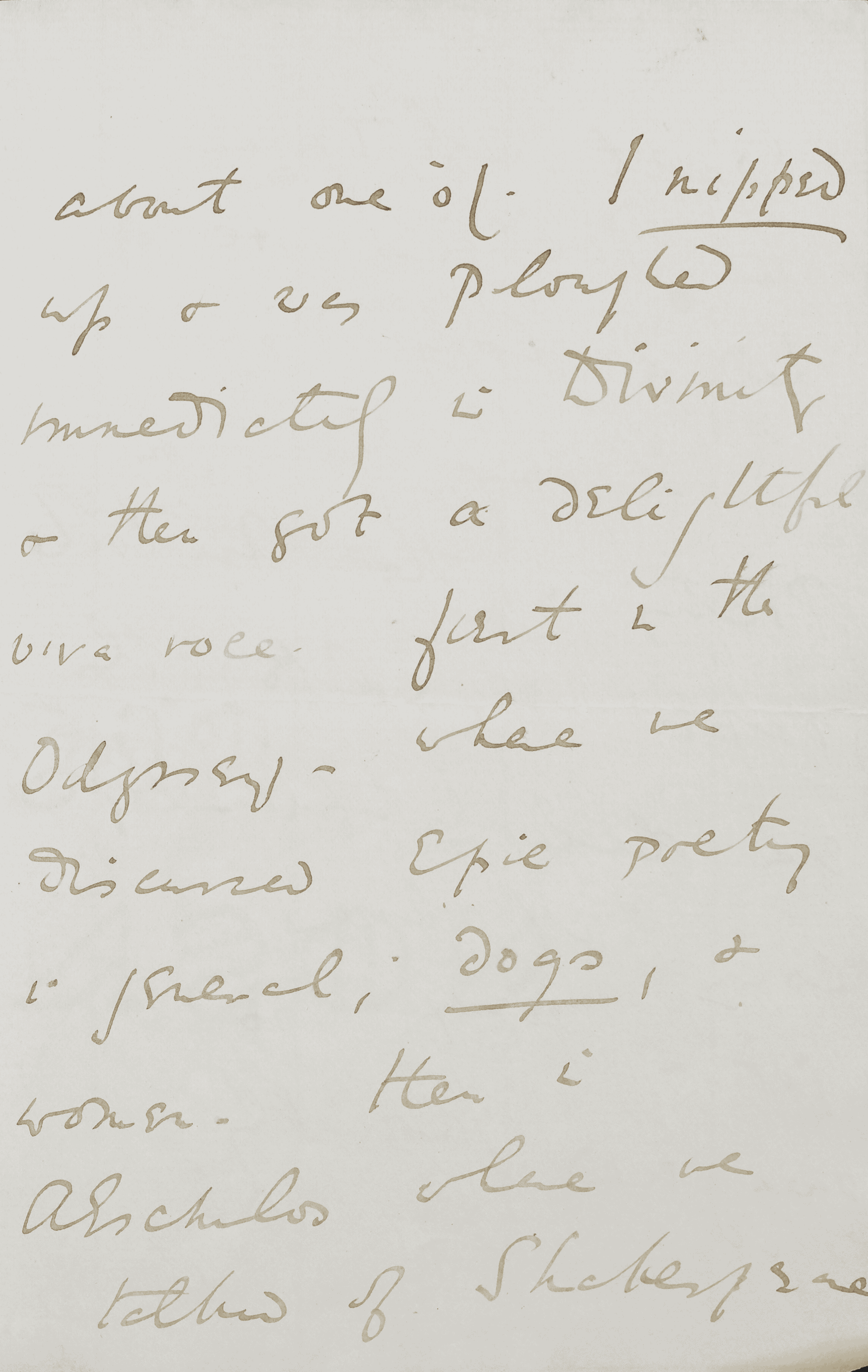

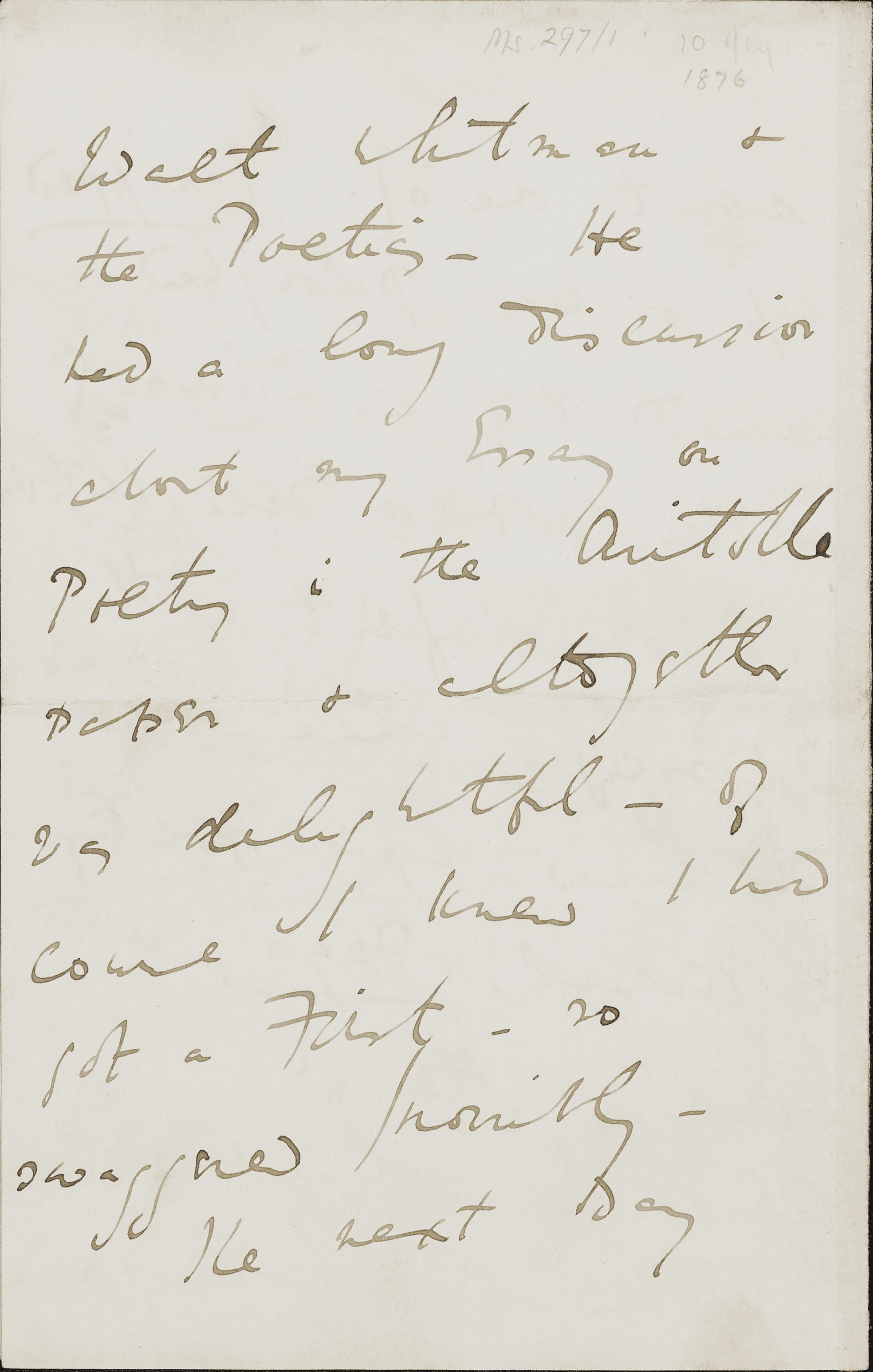

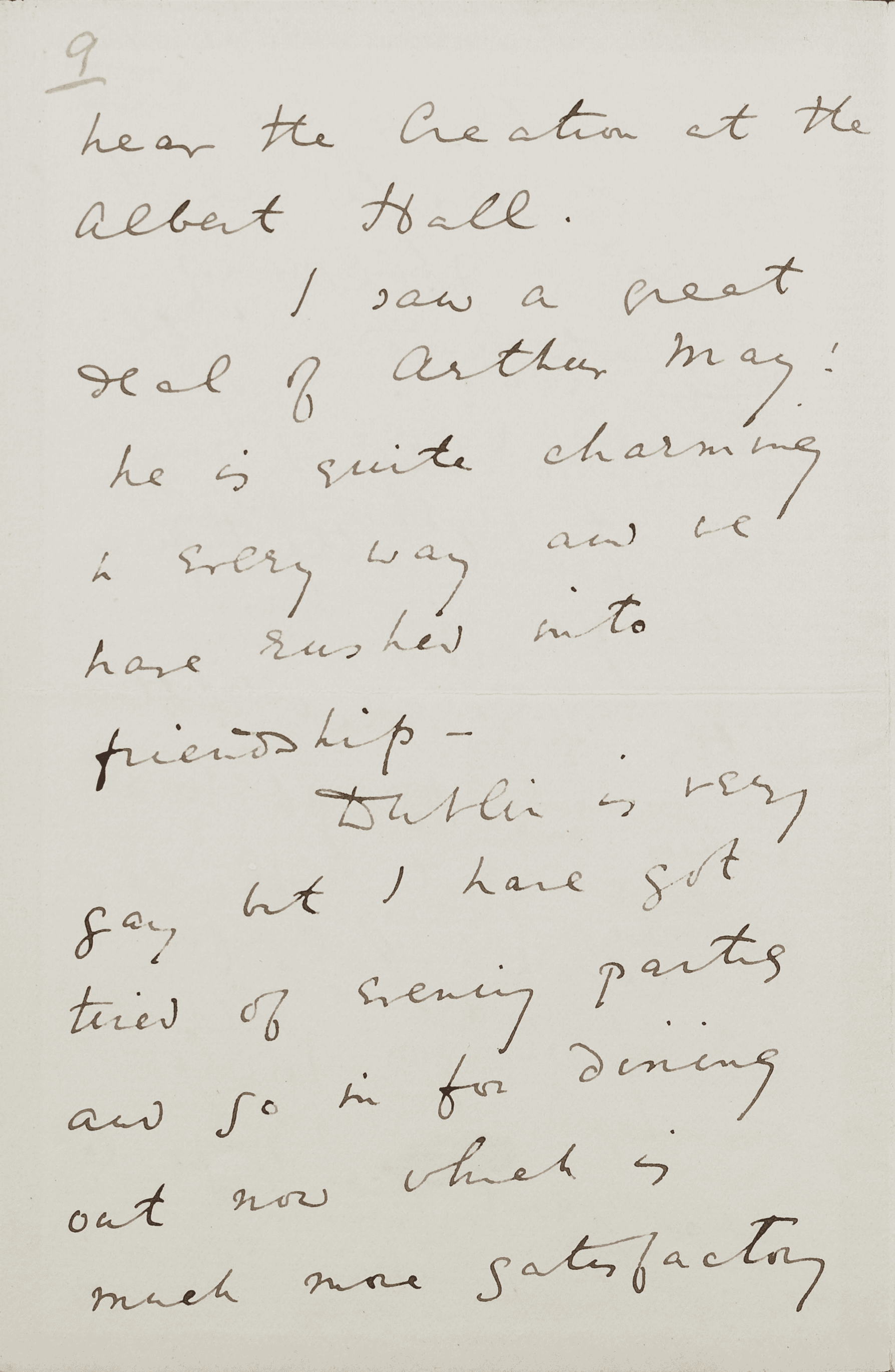

Letter from Wilde to Ward (10 July 1876)

Wilde received news of his First in Mods (first public examinations as part of his degree) and wrote at once to Ward. With customary bravado, Wilde “swaggered horribly” about his results, but to his best friend, he revealed the pain beneath. Wilde’s father had died in April, and Wilde told Ward “I think God has dealt very hardly with us”.

Magdalen College Archives, MS 297/1

The gift of Miss Cecil Ward

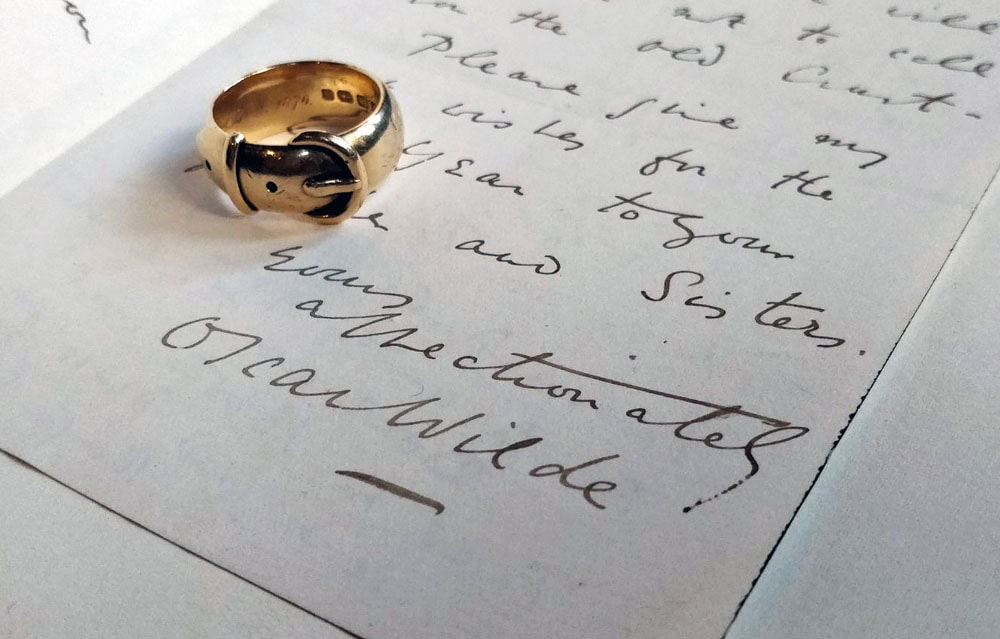

Ring given by Oscar Wilde and Reginald Harding to William Ward

For Christmas 1876, Wilde and another Magdalen friend, Reginald Harding, presented Ward with a gold friendship ring designed like a buckled belt. Stolen from Magdalen in 2002, the ring was found and returned in 2019 by Dutch art expert Arthur Brand and commodities broker George Crump. The Greek inscription means “Gift of love, to one who wishes love” and carries the initials of Wilde, Harding, and Ward’s initials: “OFOFWW + RRH to WWW”.

Magdalen College Archives

The gift of Miss Cecil Ward

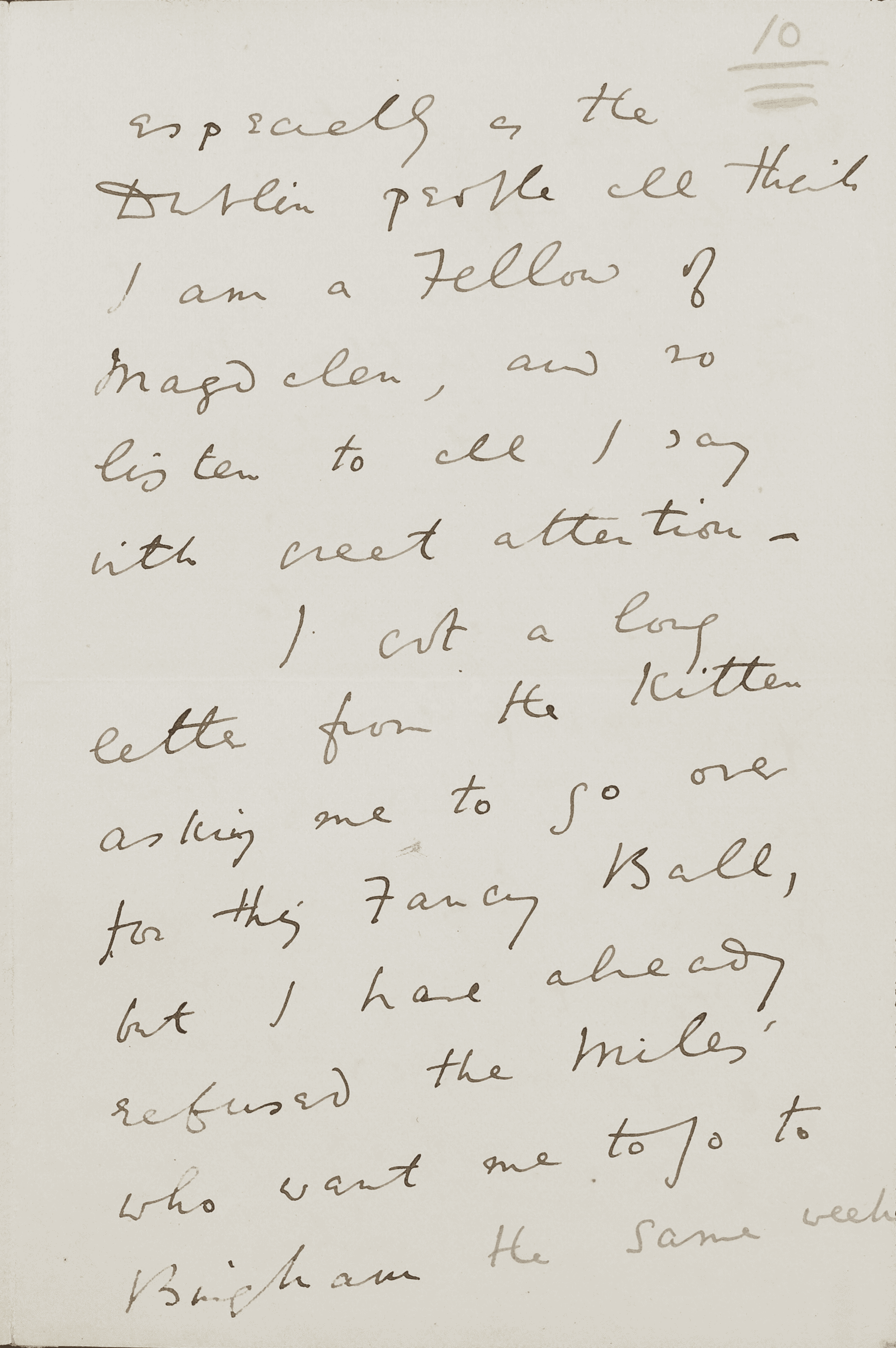

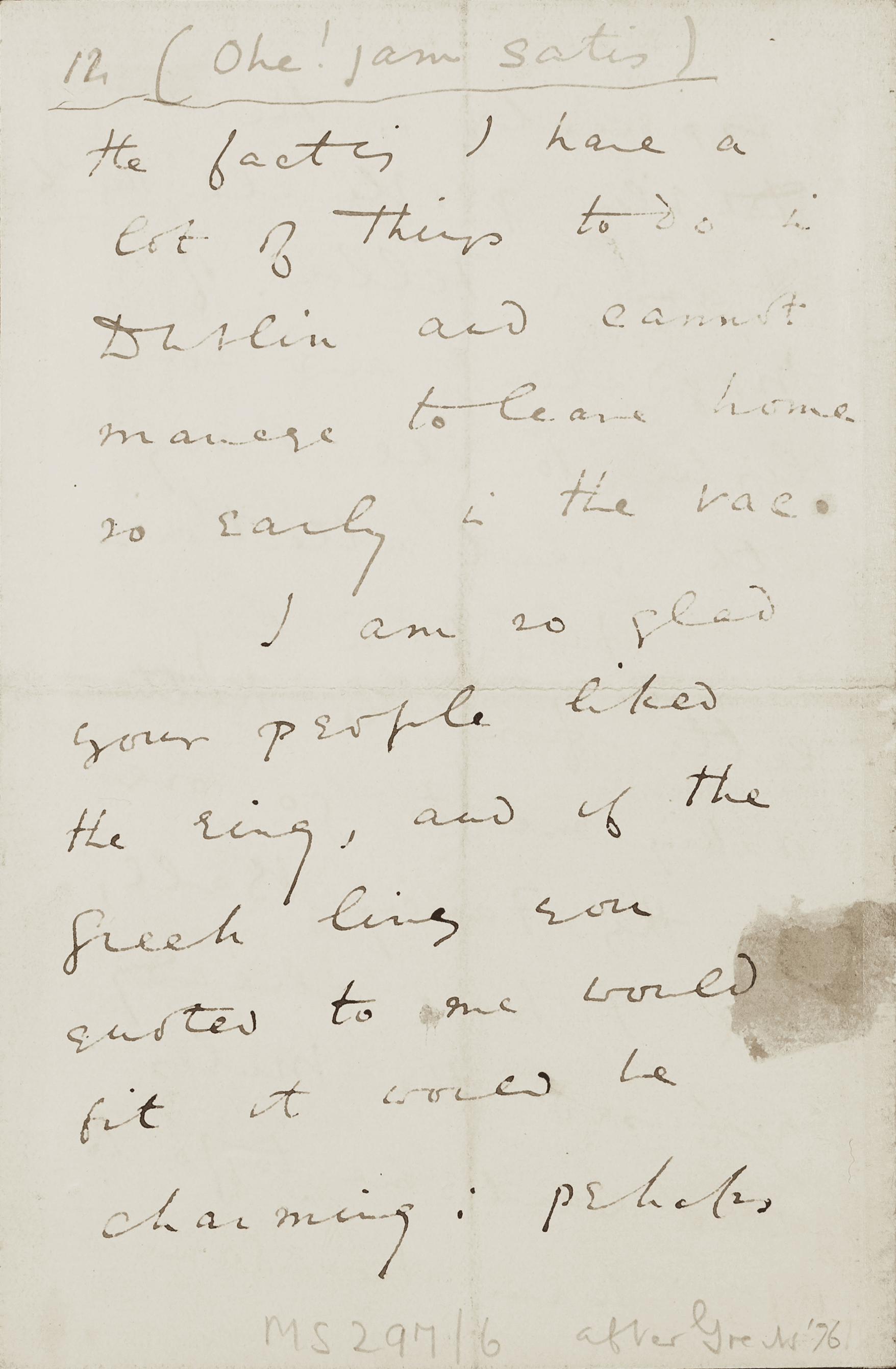

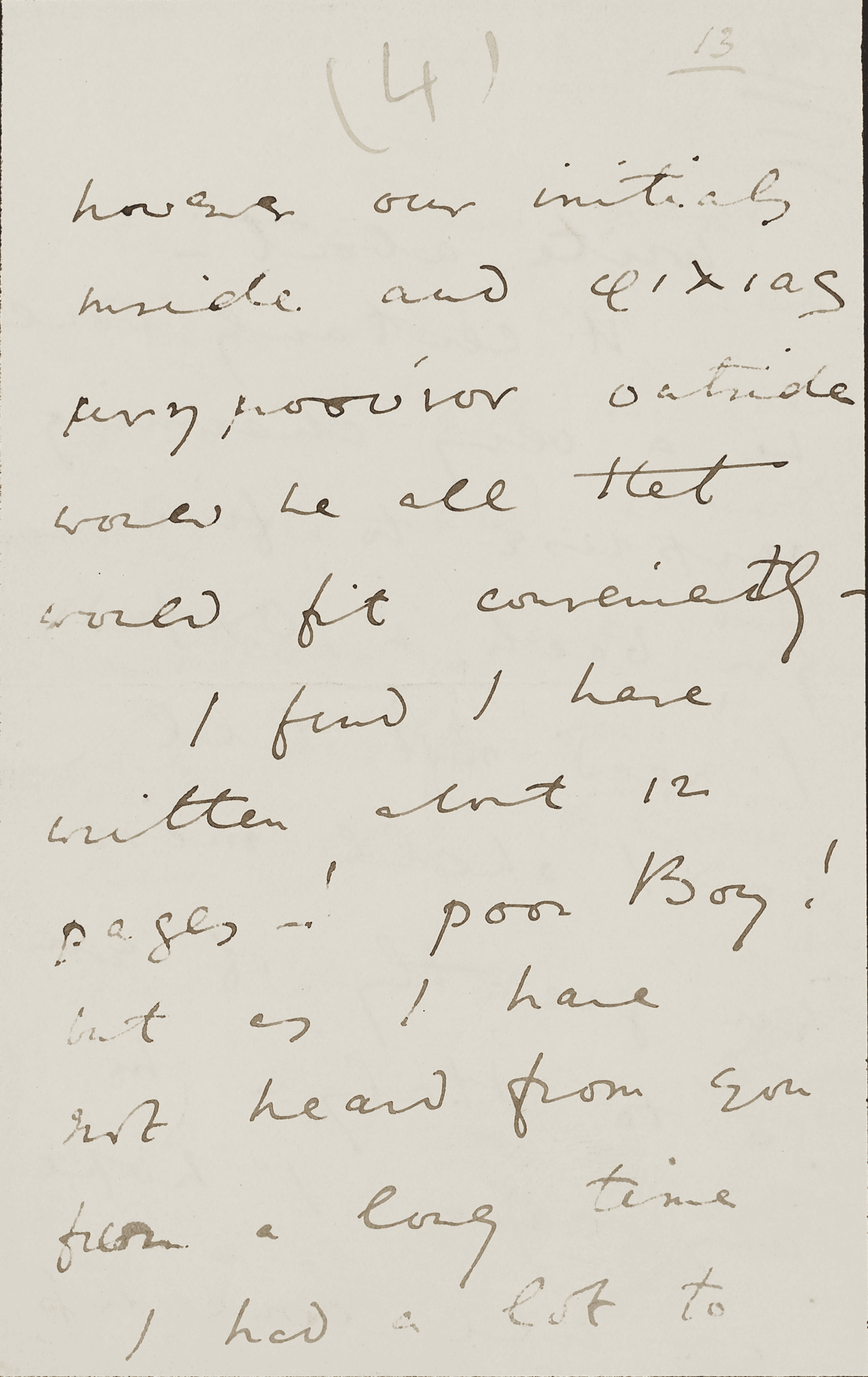

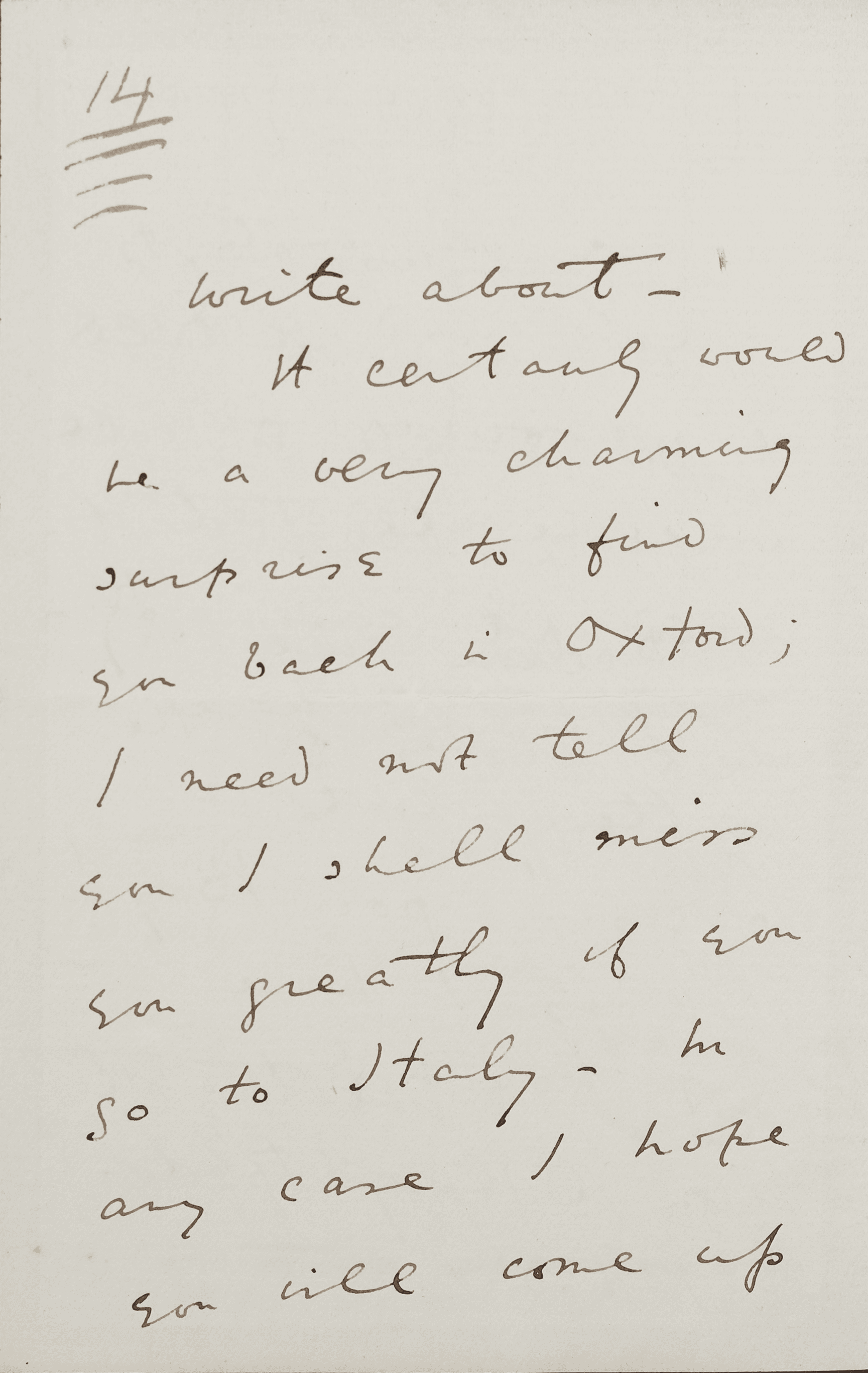

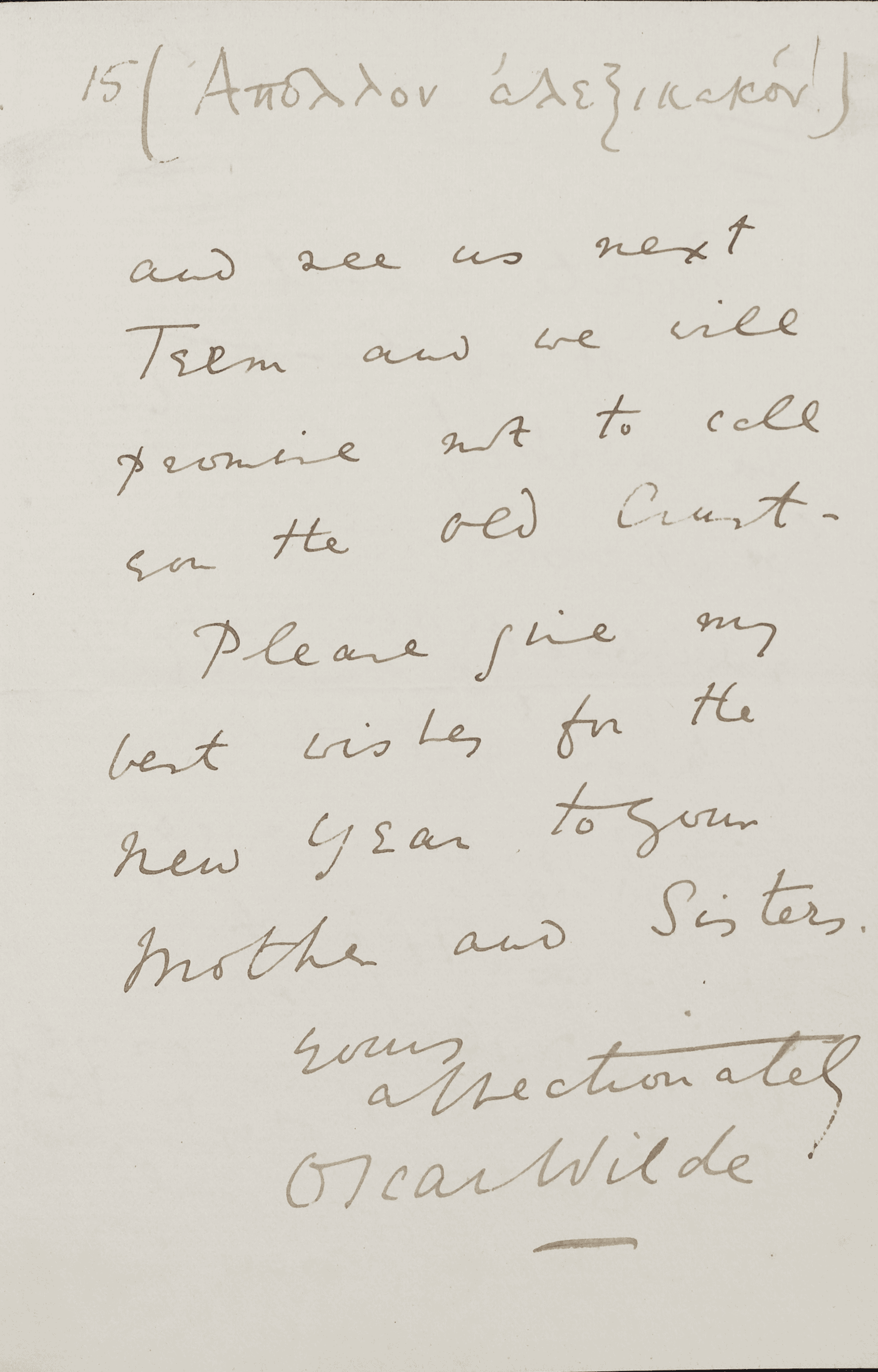

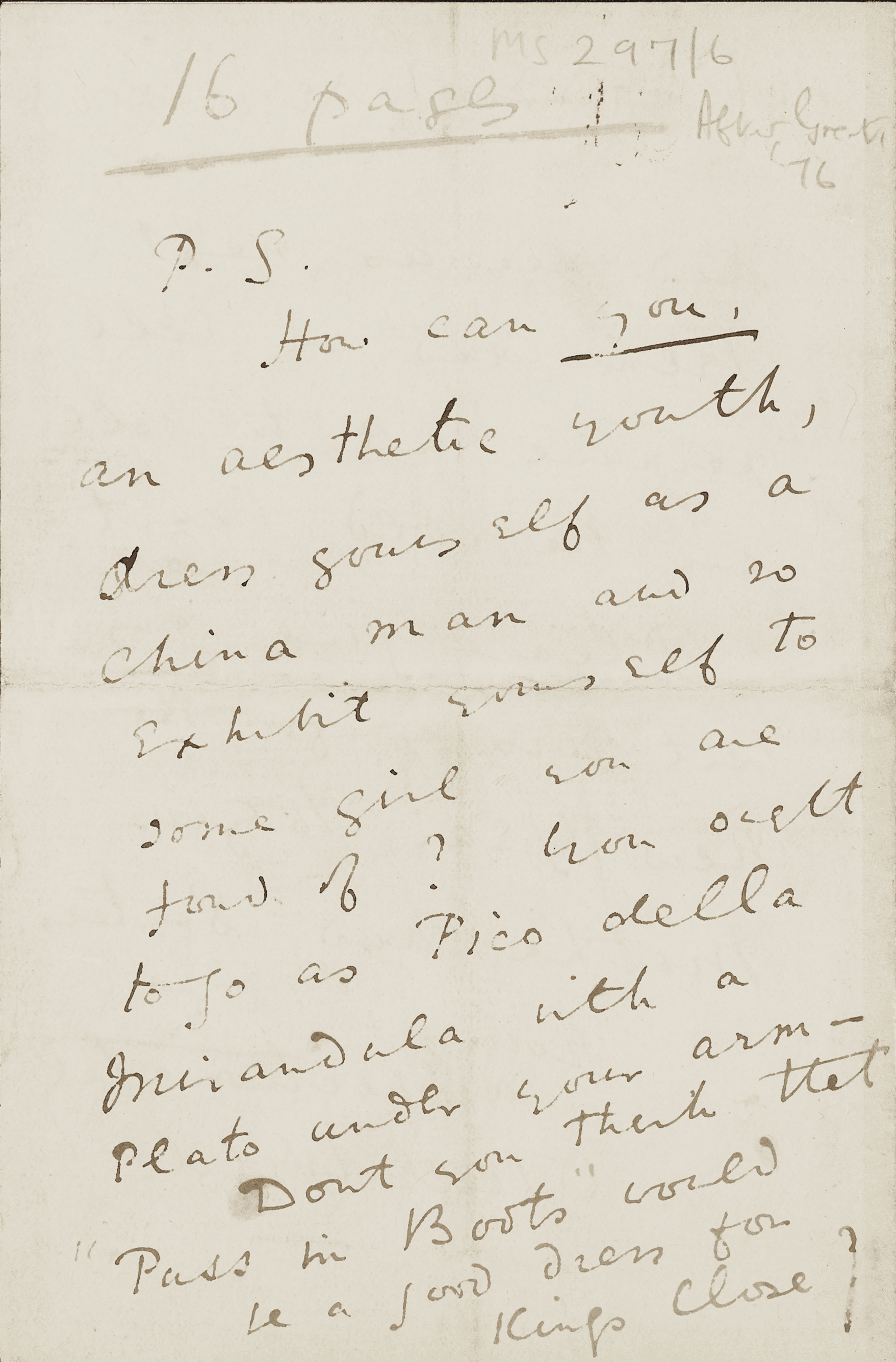

Letter from Oscar Wilde to William Ward (c. 30 December 1876)

In this letter, Wilde and Ward discuss the ring’s engraving: Ward had suggested the Greek quotation, and Wilde that their initials should appear.

Magdalen College Archives, MS 297/6

The gift of Miss Cecil Ward

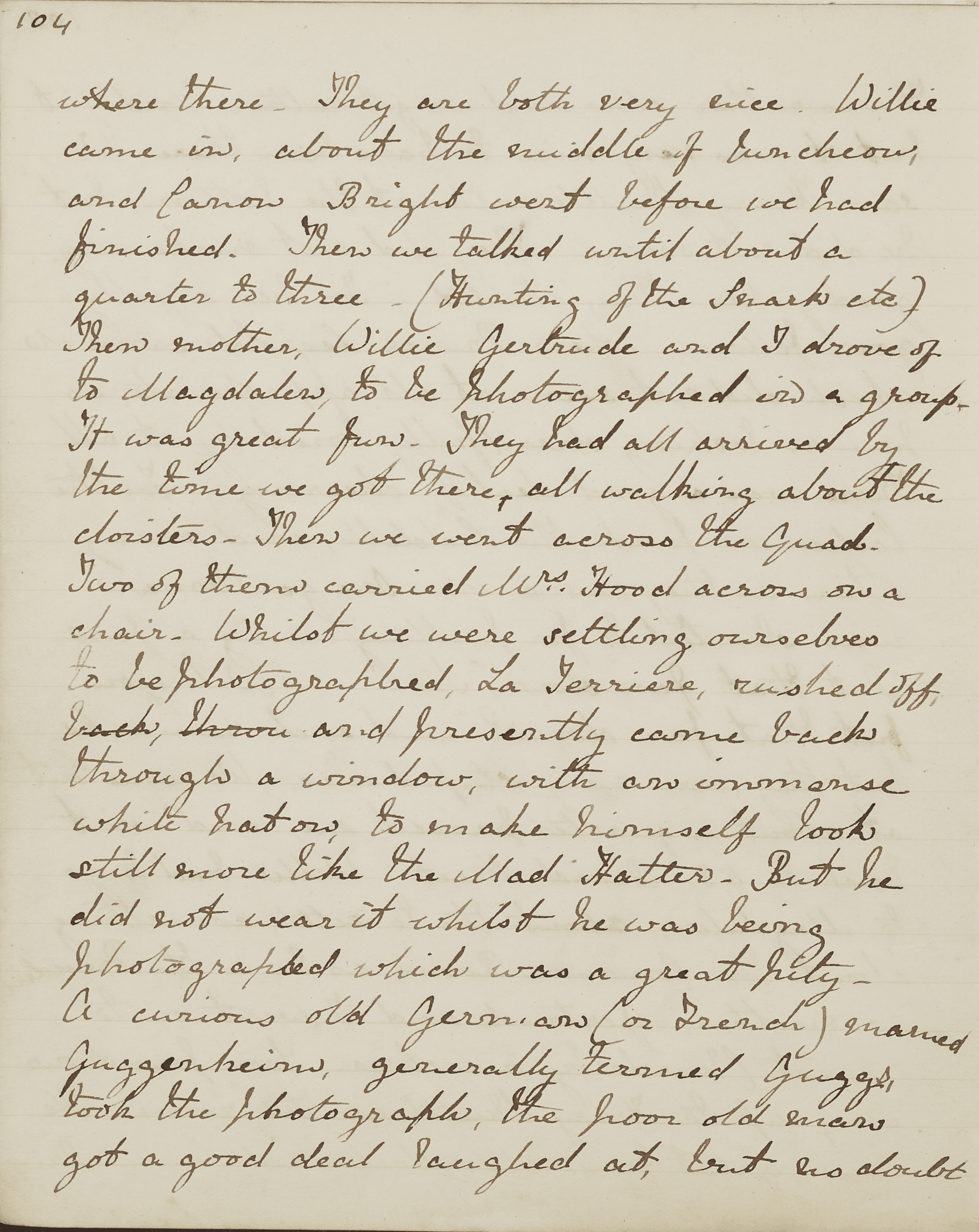

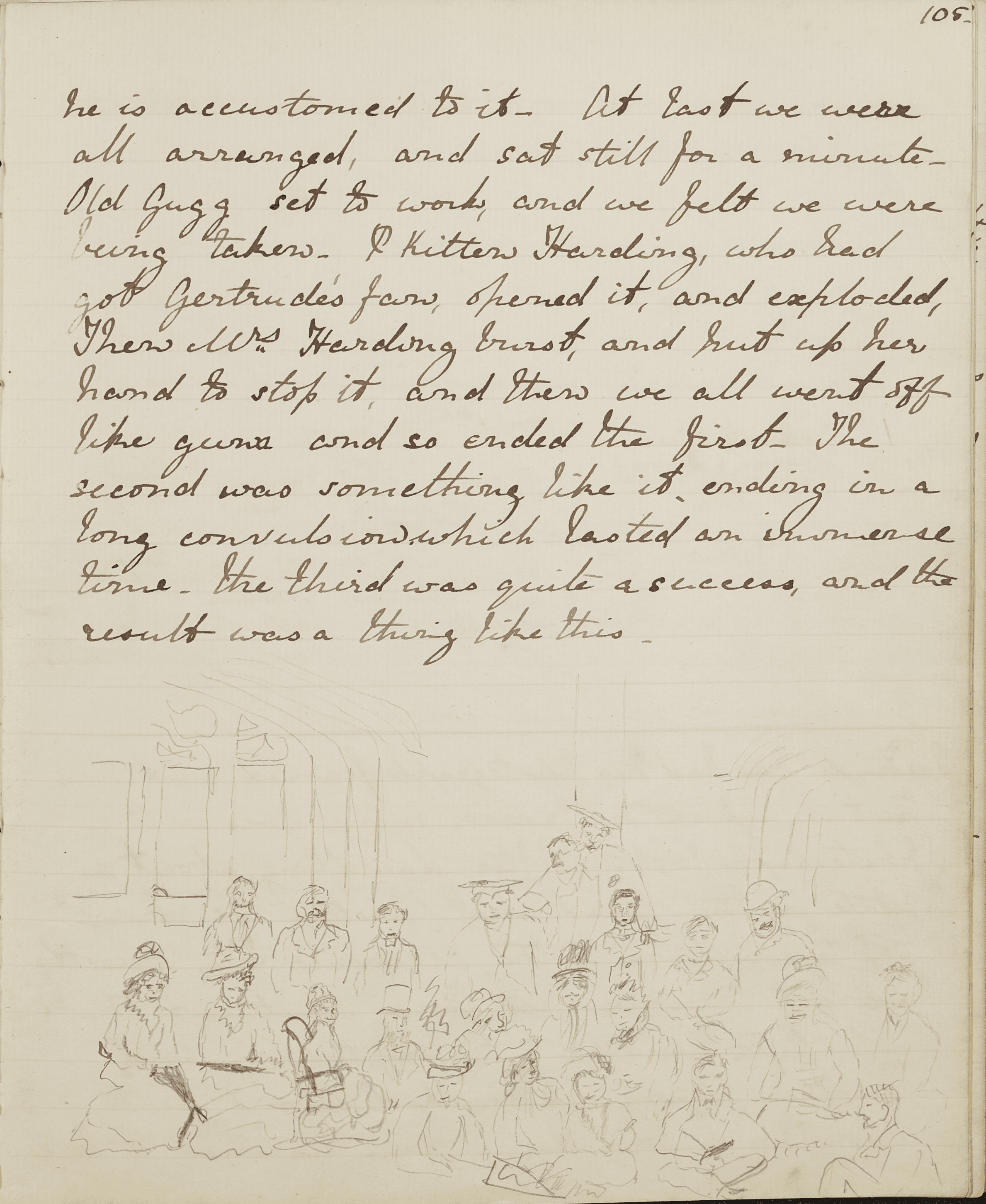

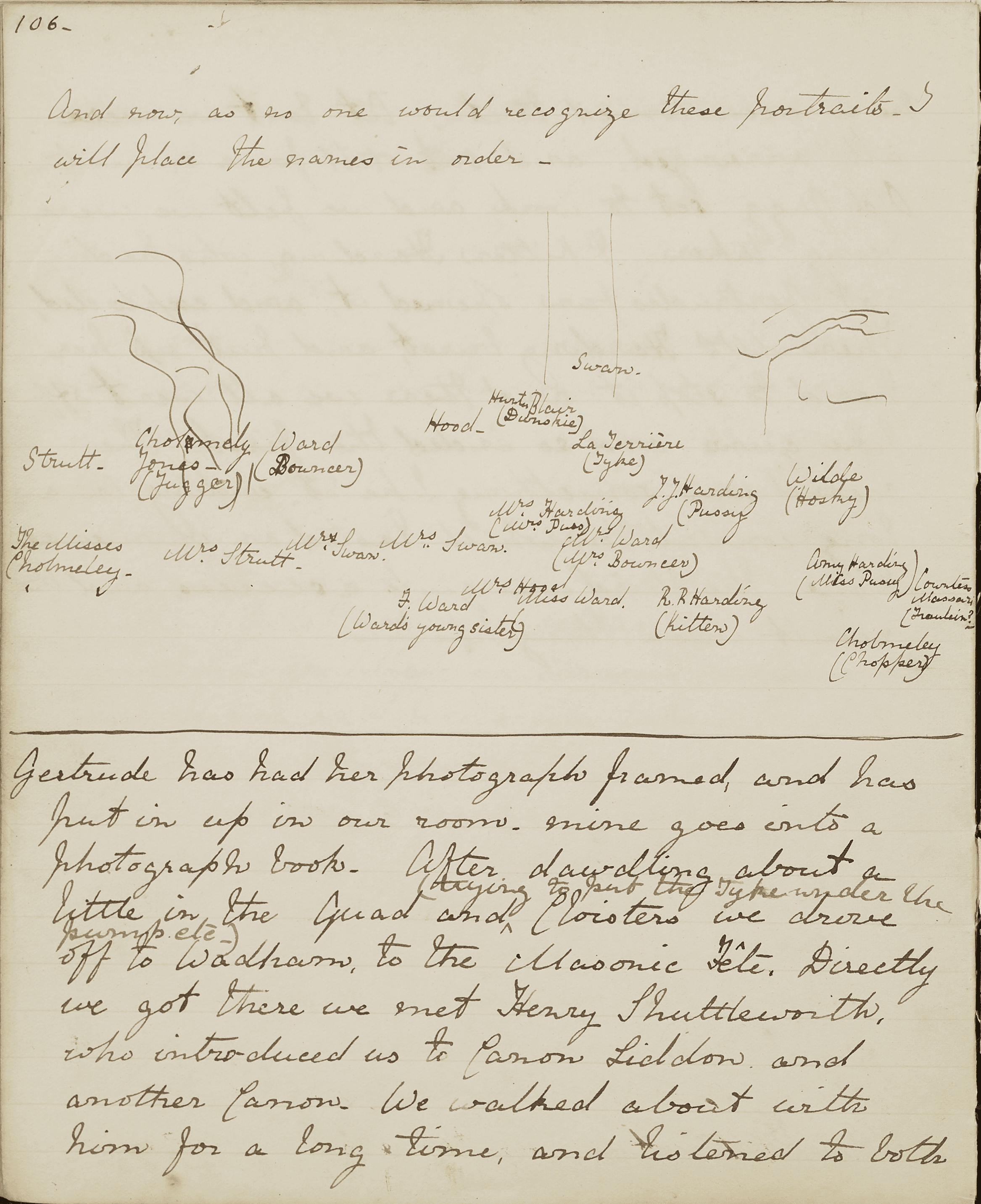

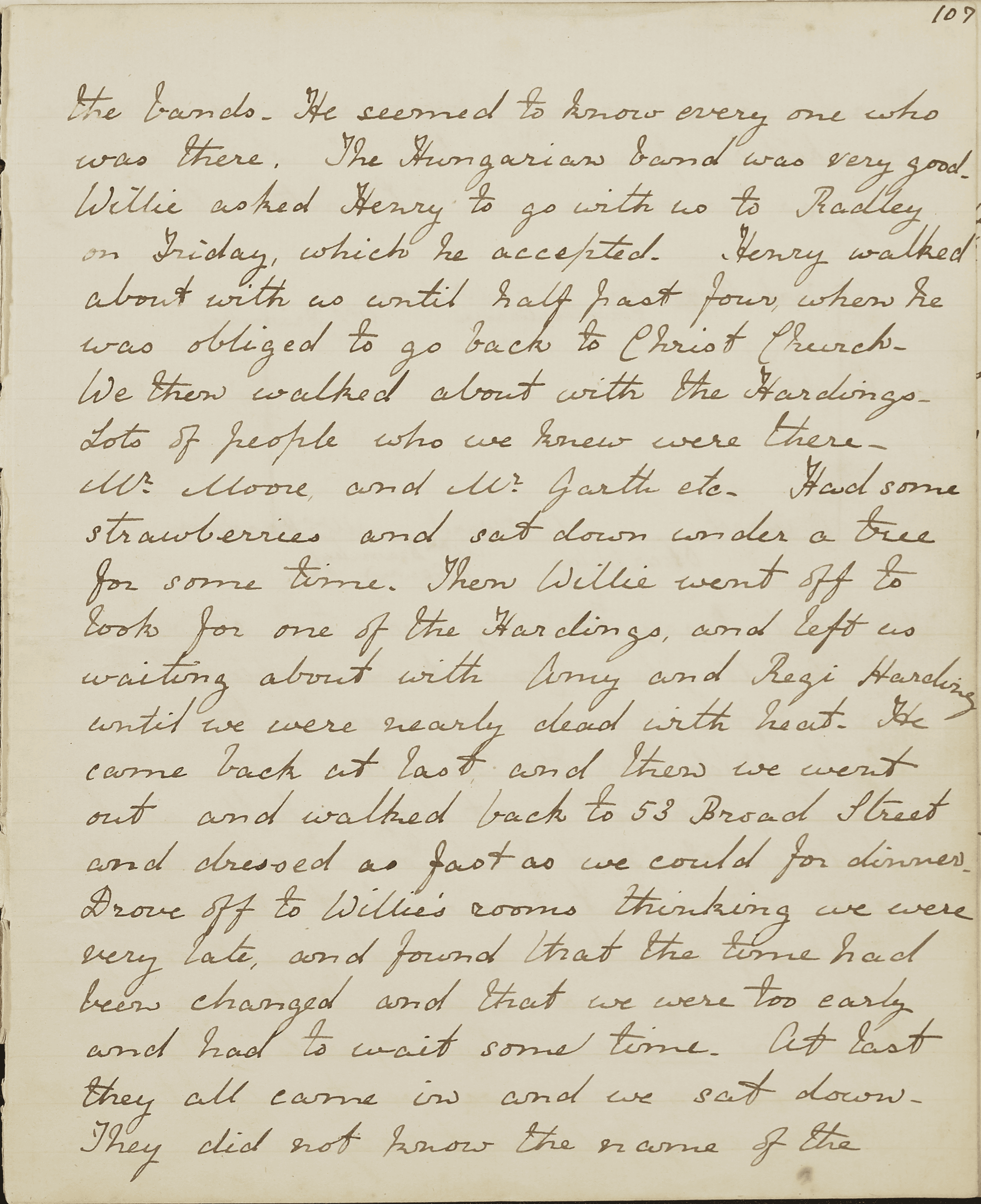

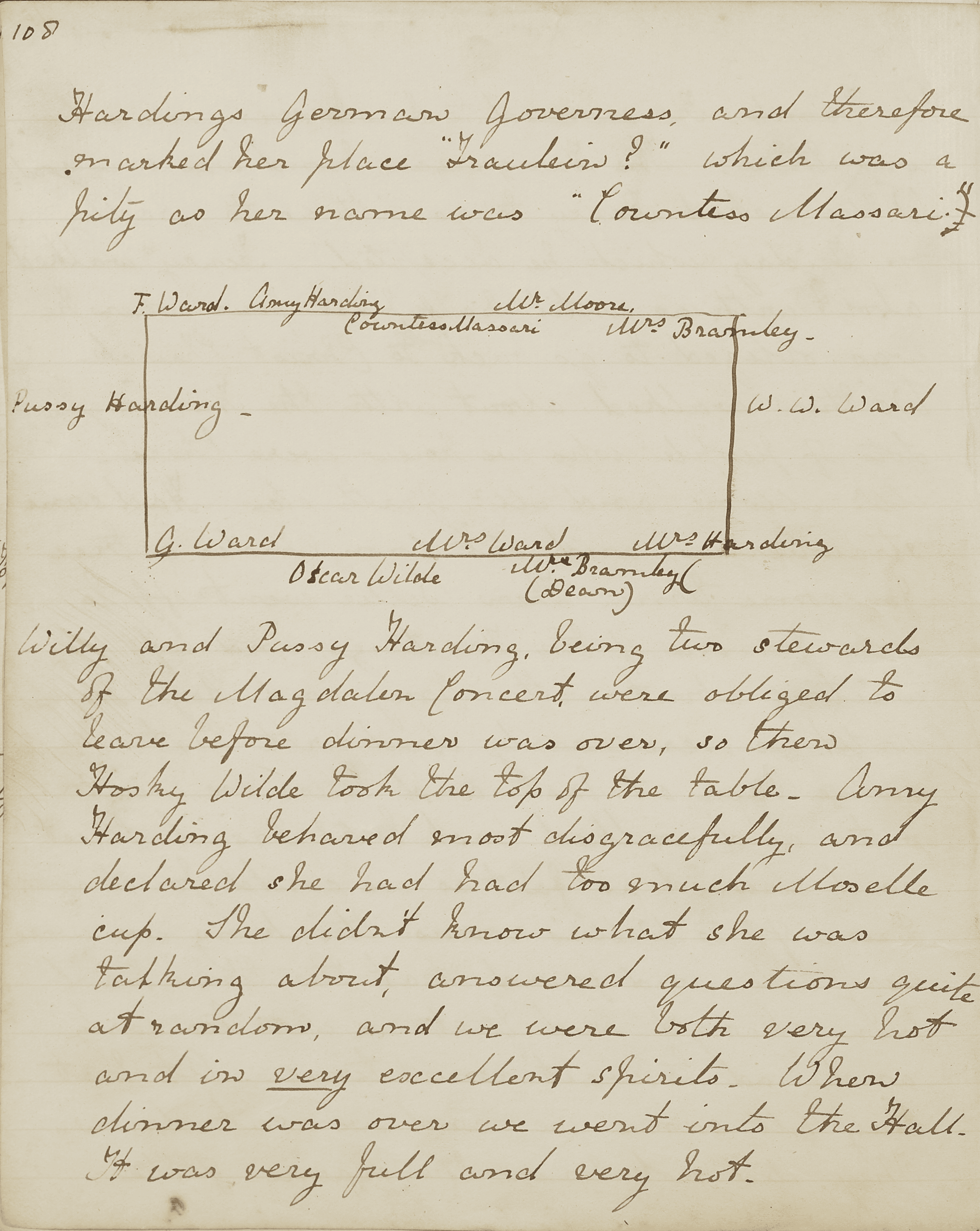

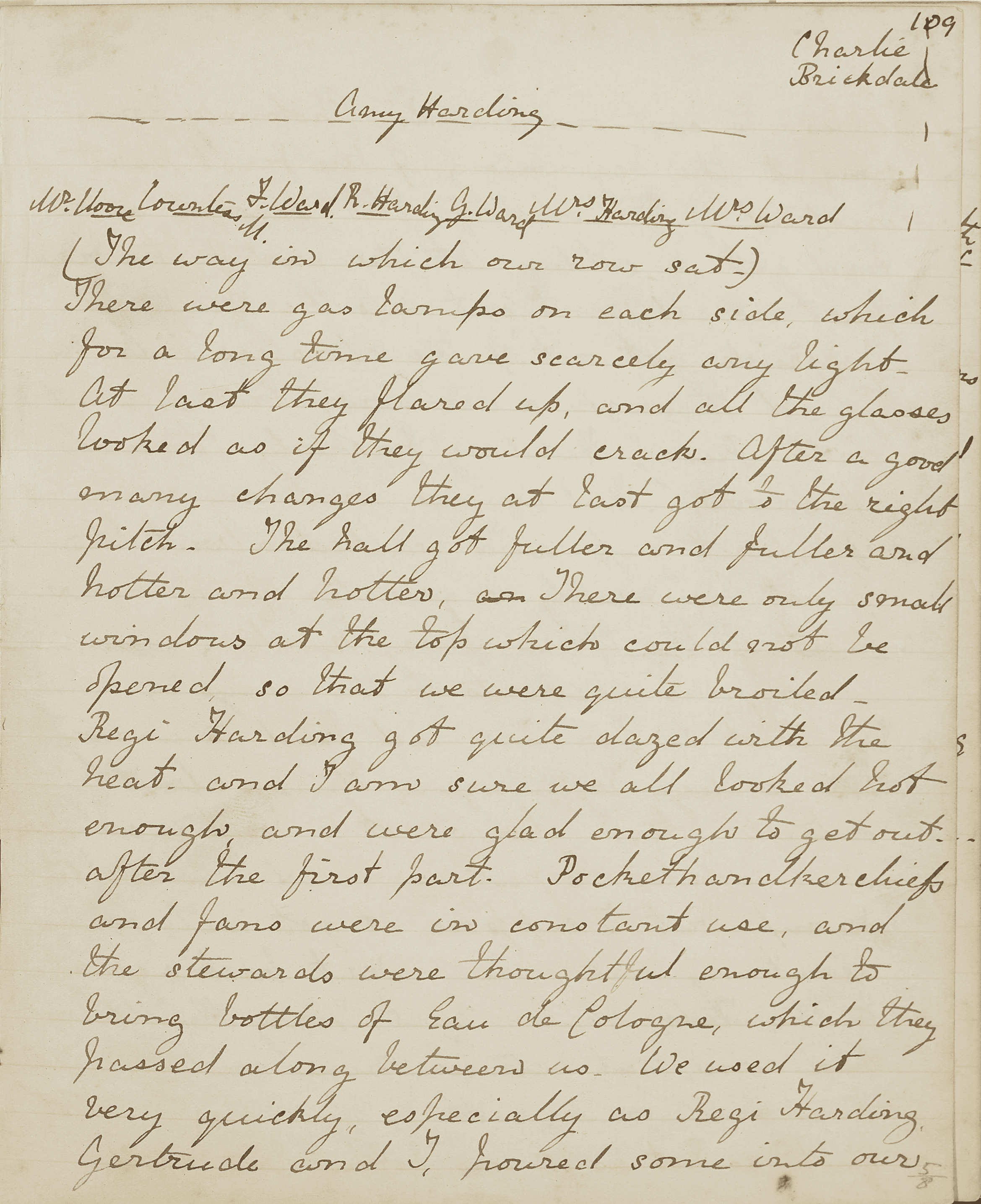

The Diary of Florence Ward

William Ward’s younger sisters (Gertrude and Florence) visited their brother in Oxford in June 1876 for Commemoration Week. 16-year-old Florence’s diary includes sketches, visits to Blenheim and Radley, and attendance at balls and concerts – all with Wilde. He even introduced the girls to champagne cocktails! Wilde liked the family hugely; there was also a suspected flirtation between Wilde and Gertrude Ward.

Magdalen College Archives, MS 618

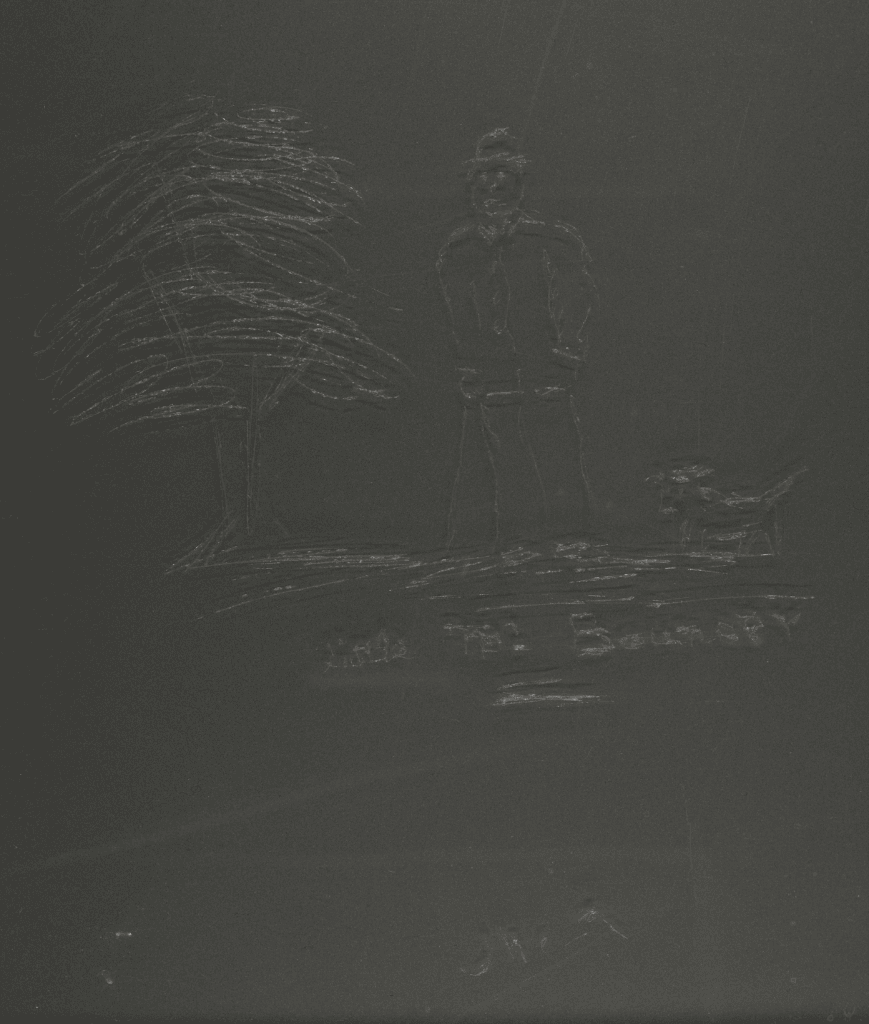

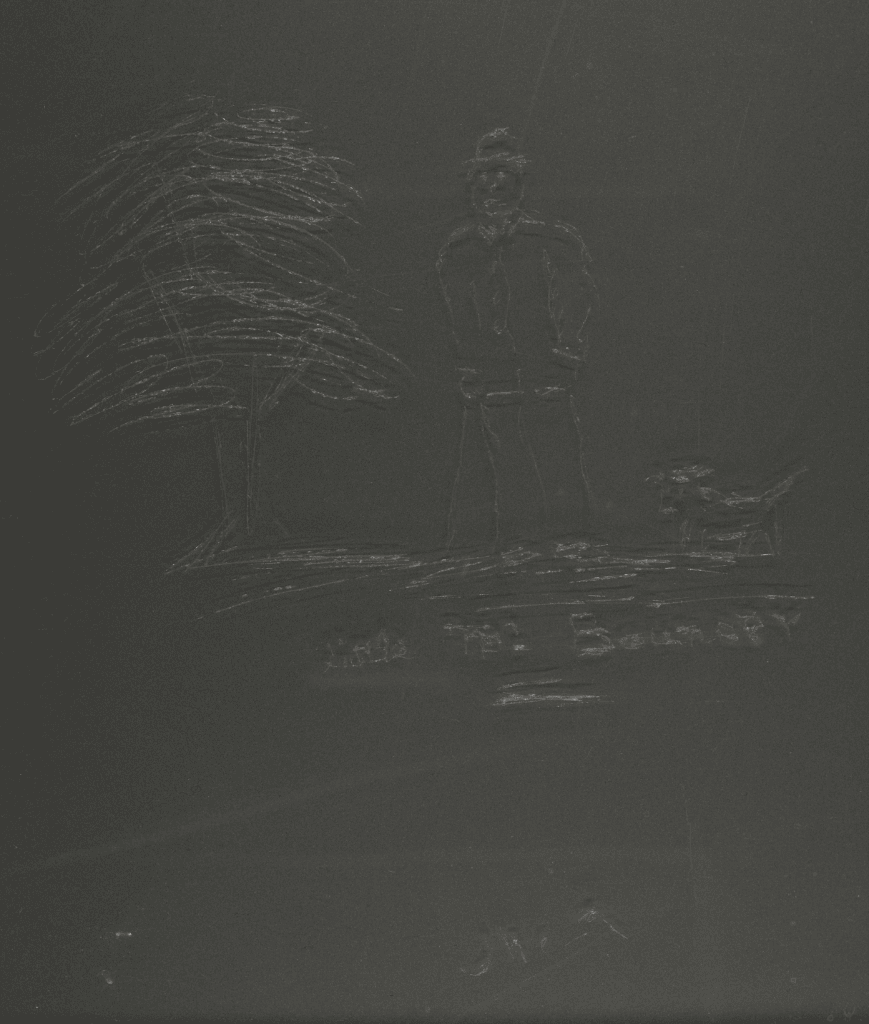

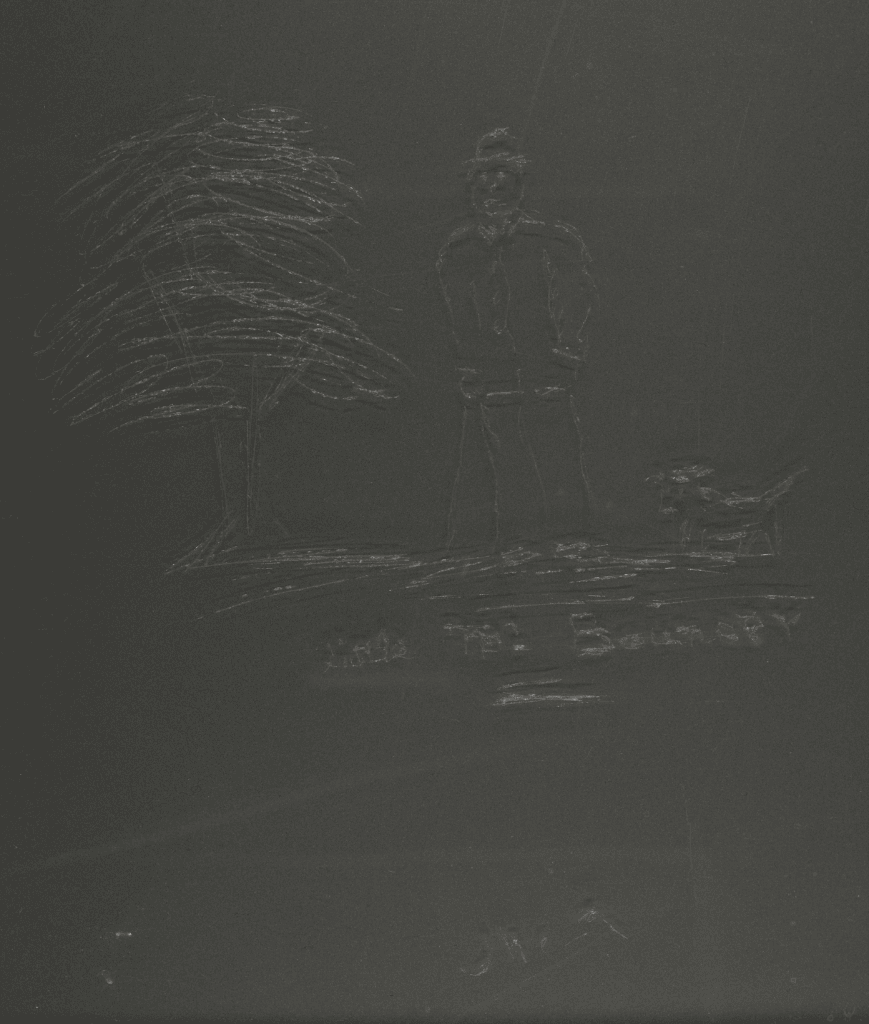

Drawing of “Little Mr Bouncer” by Wilde (c. 1874–6)

Wilde scratched this picture of Ward on the window of what is today known as the “Oscar Wilde Room”: the student room Wilde inherited from Ward after Ward graduated in 1876. Because of Ward’s diminutive stature, his Magdalen friends nicknamed him “Bouncer” after the 1855 children’s novel Little Mr Bouncer And His Friends. This drawing was rediscovered by the College Works Department in 2003.

Magdalen College Archives

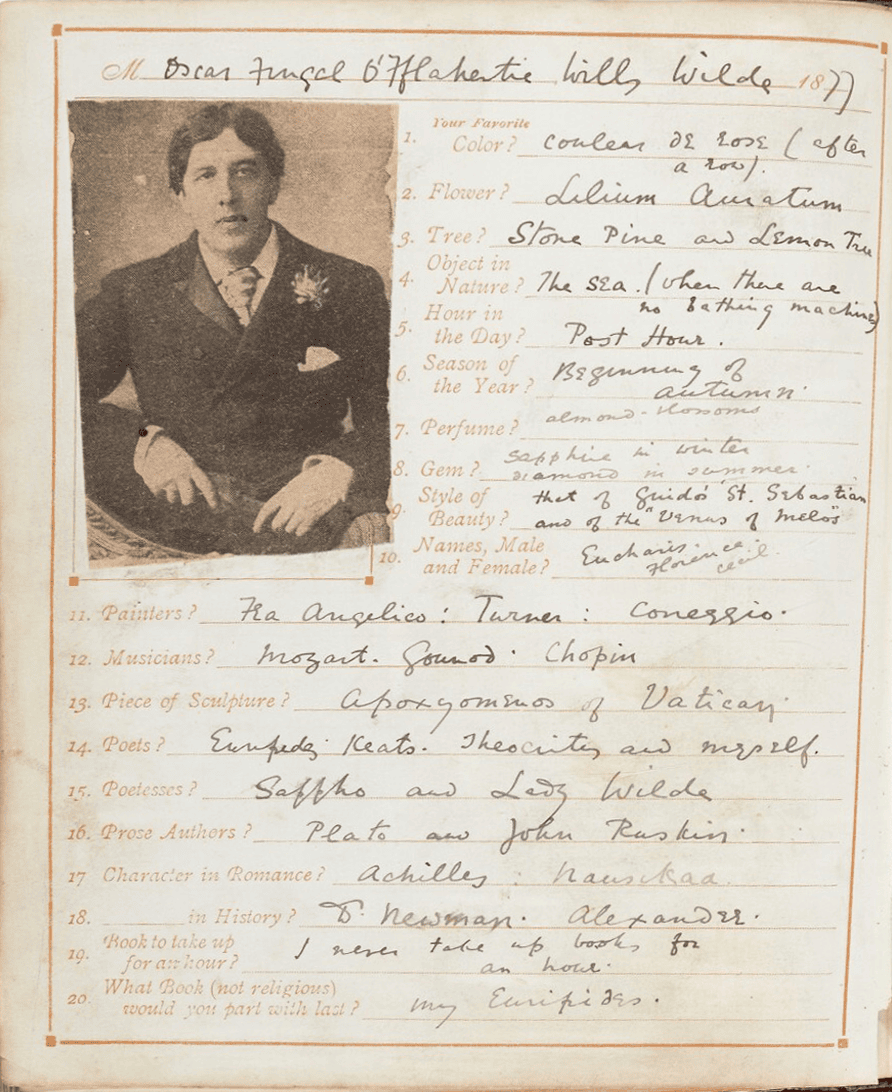

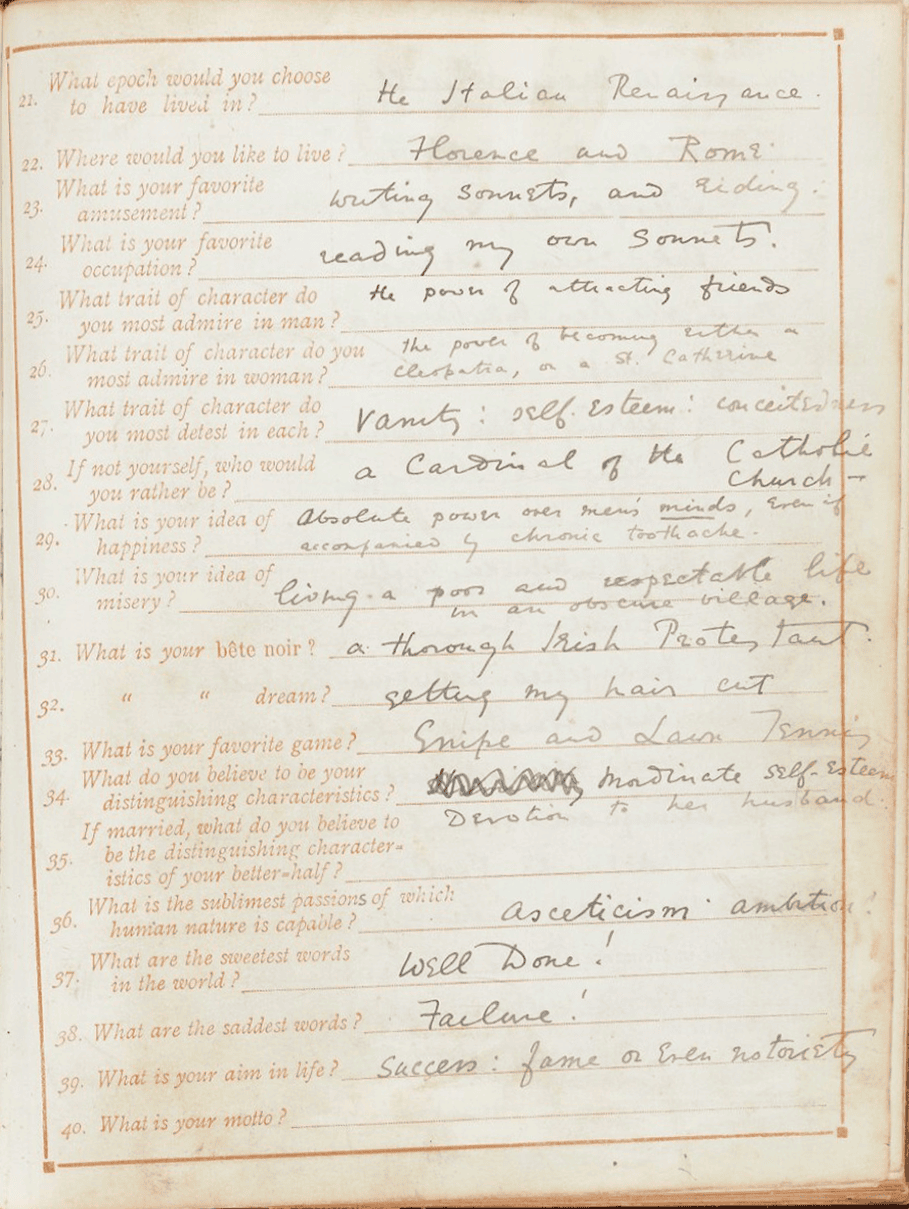

“What are the Sweetest Words in the World?”

In 1877, Wilde filled in a questionnaire in Adderley Millar Howard’s ‘Album for Confessions or Tastes, Habits and Convictions’. The facsimile reveals the young Wilde’s fear of failure, longing for celebrity – and, touchingly, his fondness for the name ‘Cyril’, eventually that of his eldest son

Ravenna (Oxford: Thomas Shrimpton & Son, 1878)

Wilde was late back for the summer term at Magdalen in 1877, thanks to a protracted jaunt across Europe. Magdalen sent Wilde down for two terms, which enraged him. Nonetheless, his travels gave him material for Ravenna, a poem which won the Newdigate Prize in 1878. The poem contrasts the ‘Hellenic dream’ from antiquity to Renaissance with the suffering and sensuality of Christian myth.

Magdalen College Library, Magd.Wilde-O. (RAV)

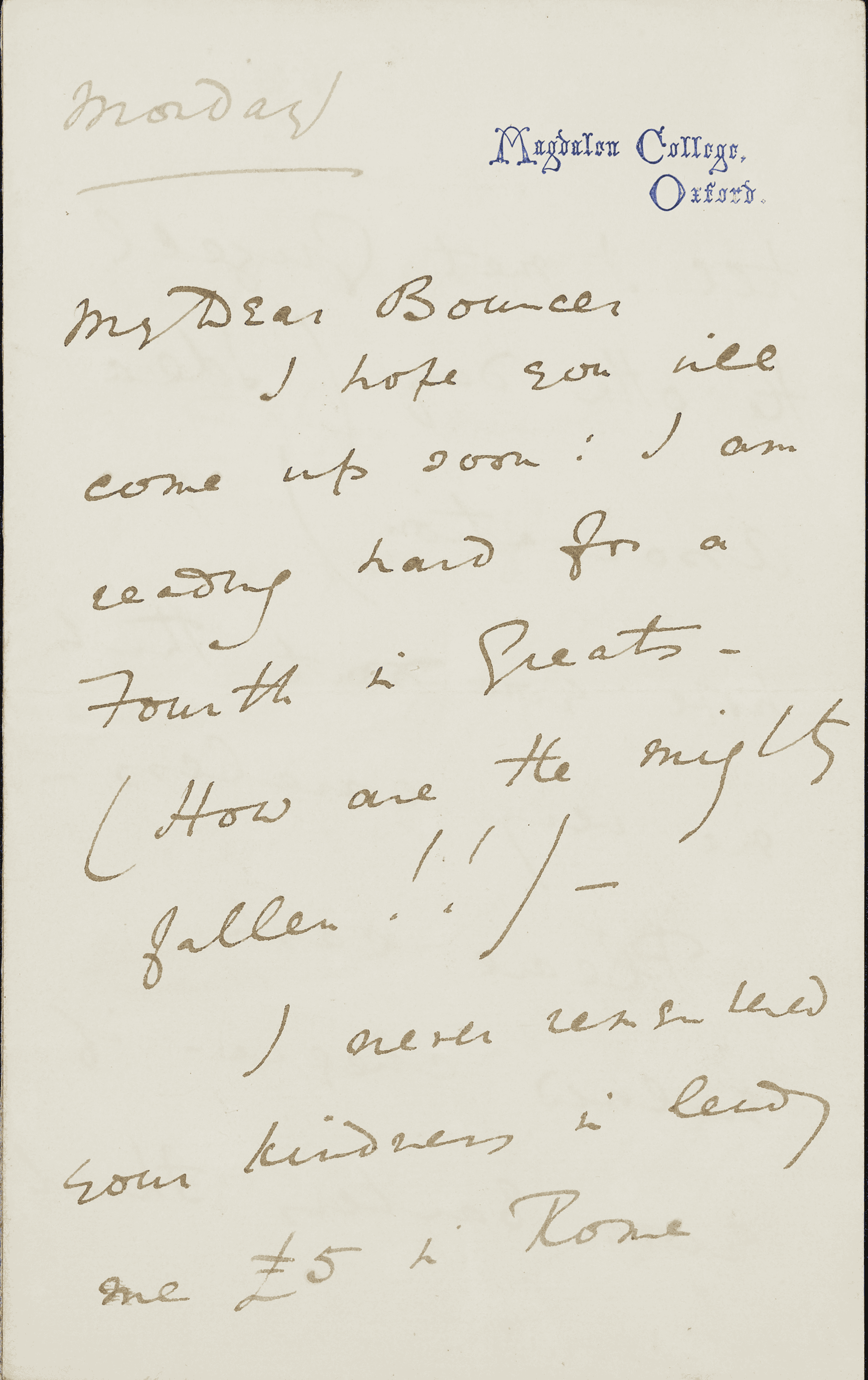

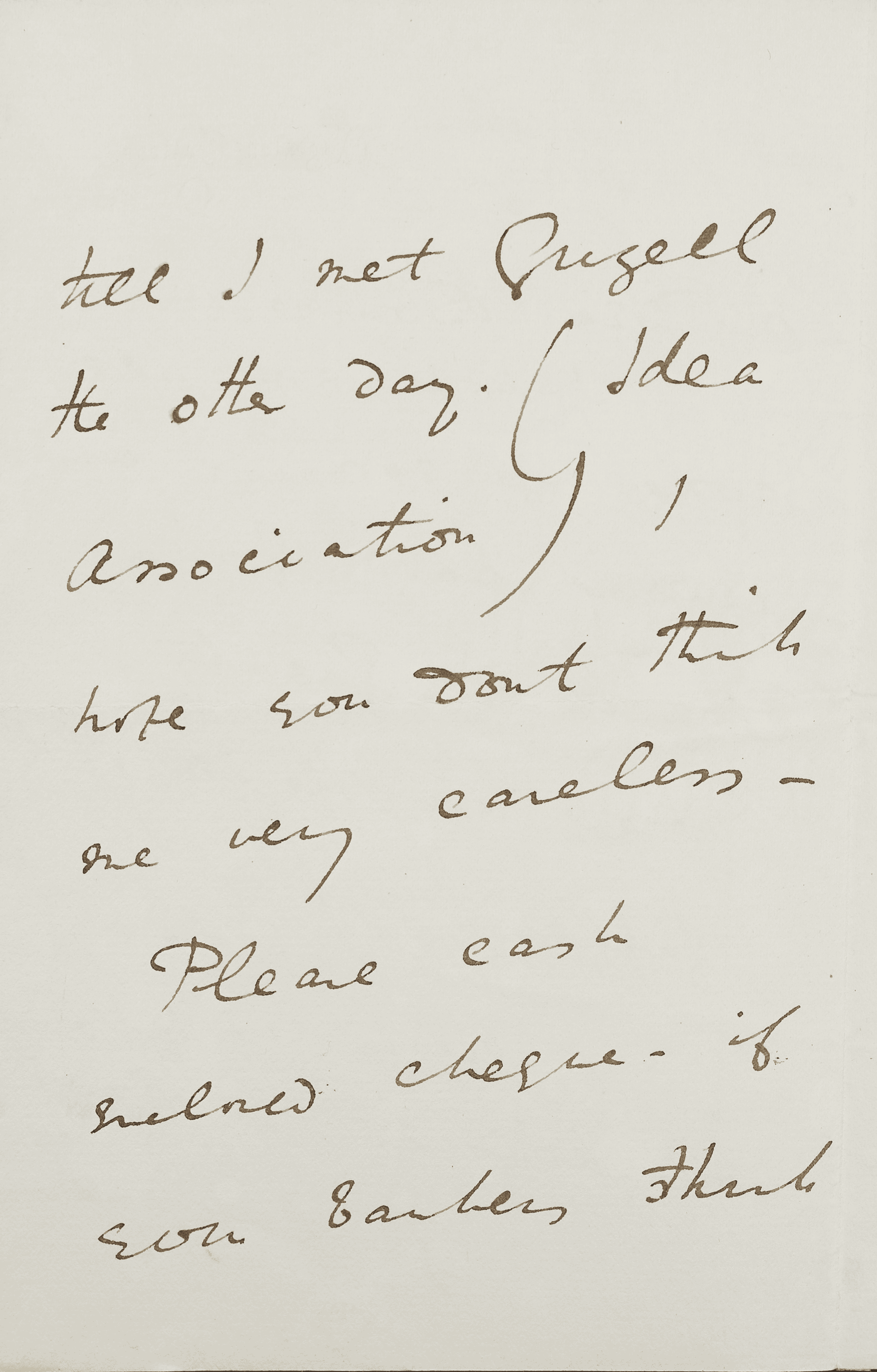

Letter from Wilde to Ward (1877)

Back at Magdalen in the autumn of 1877, Wilde was beginning to worry about Greats (Finals exams). He told Ward “I am reading hard for a Fourth in Greats (How are the mighty fallen!!)”. Wilde posed as a dilettante but in fact studied hard, reading into the small hours.

Magdalen College Archives, MS 297/13

The gift of Miss Cecil Ward

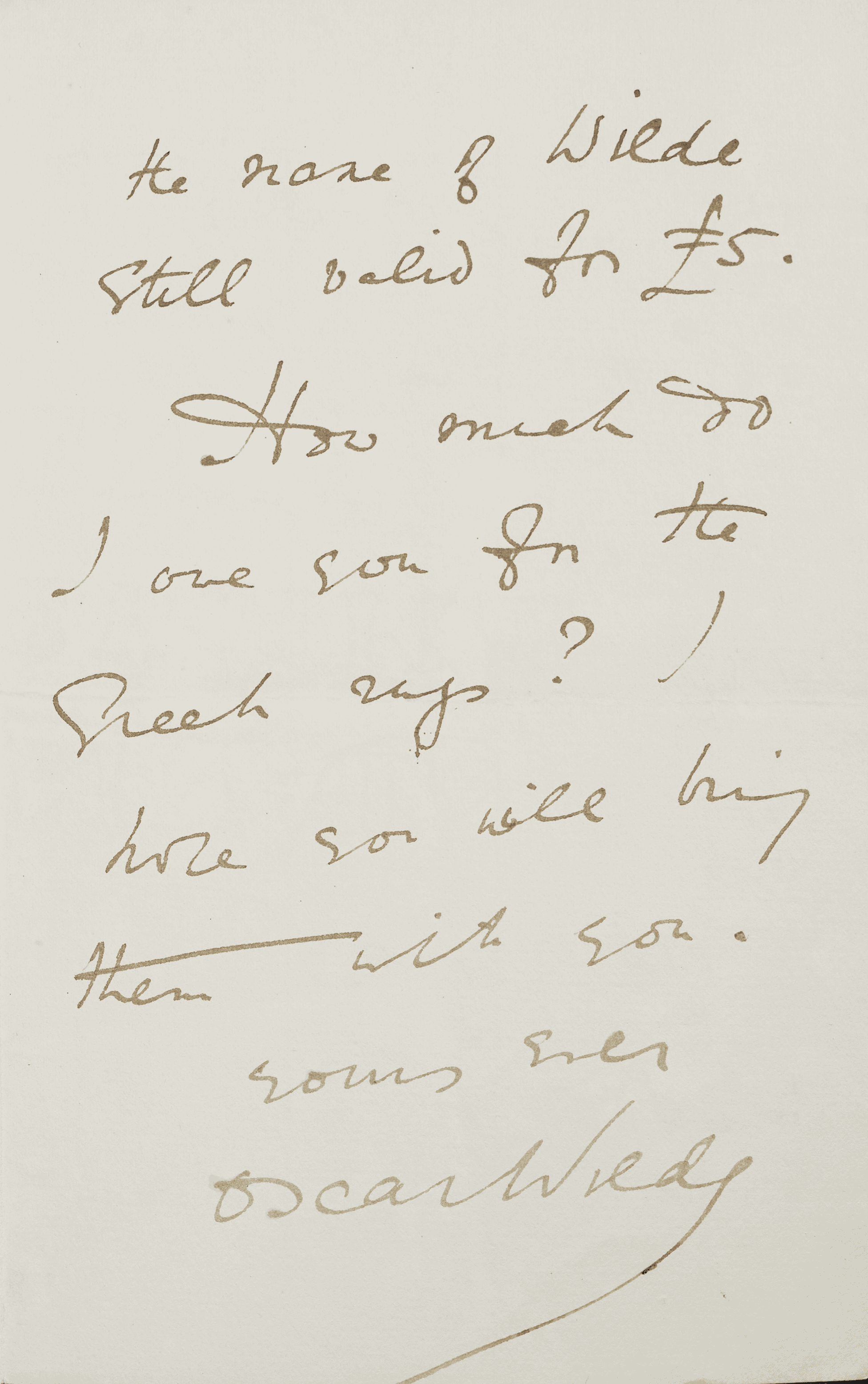

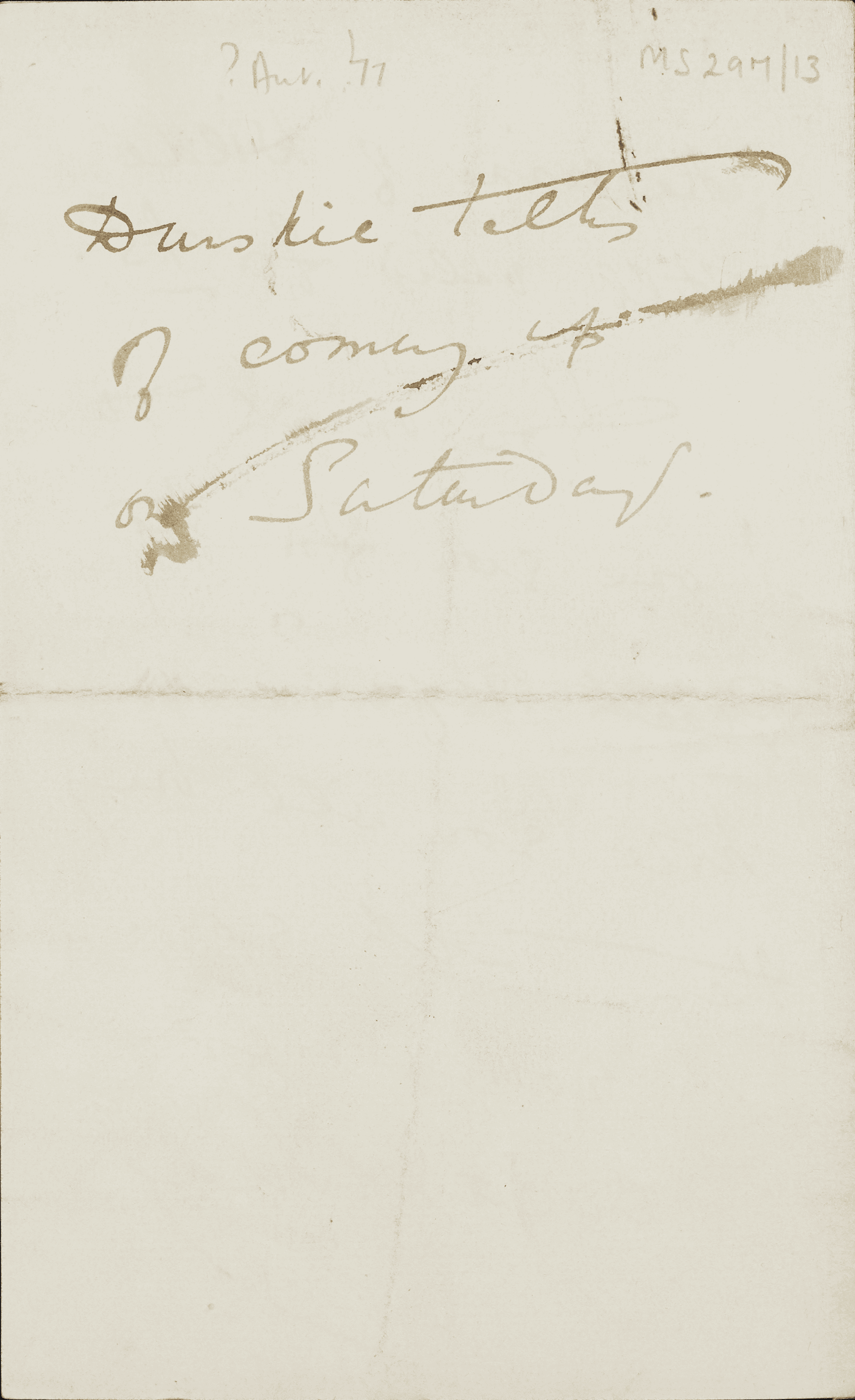

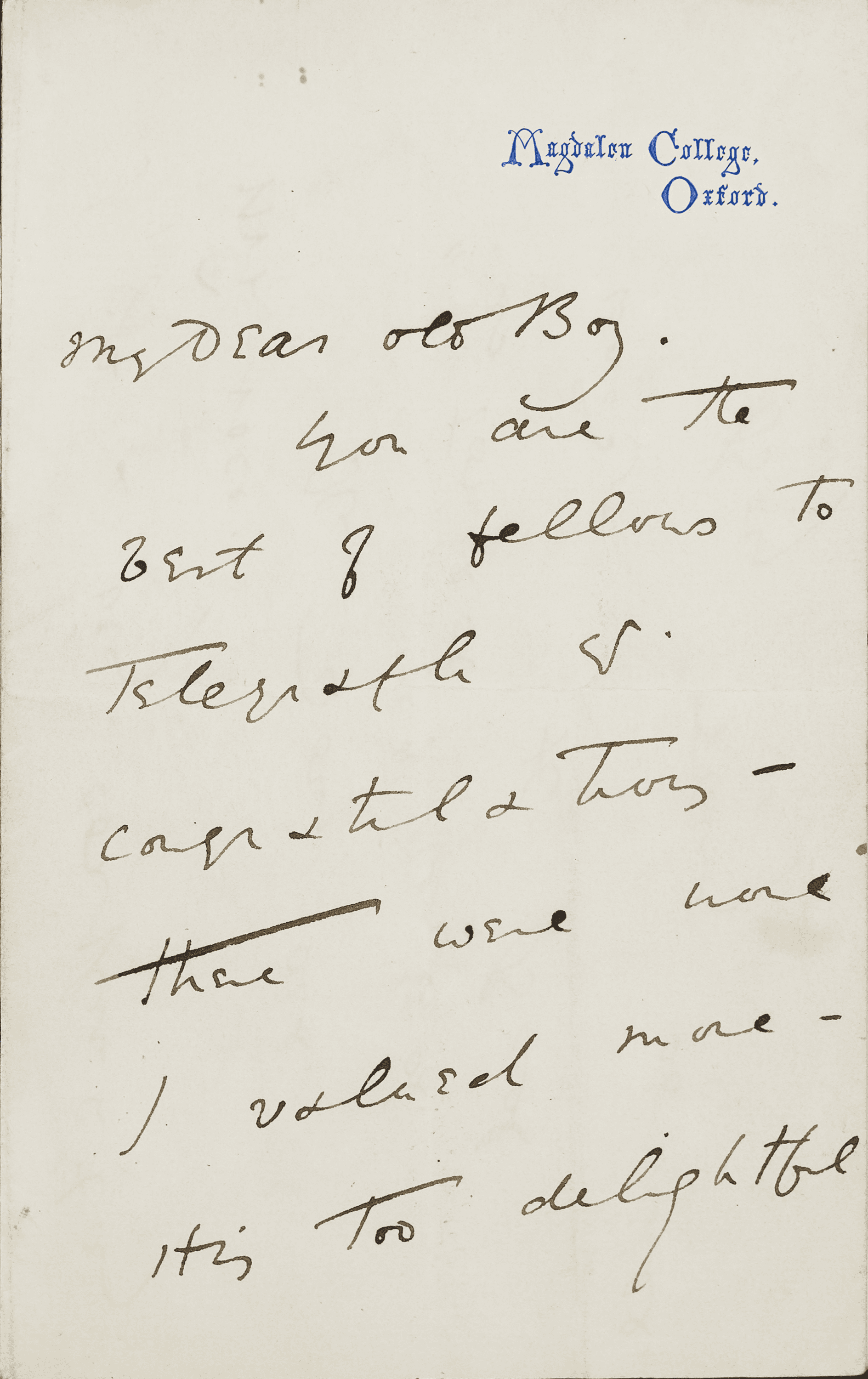

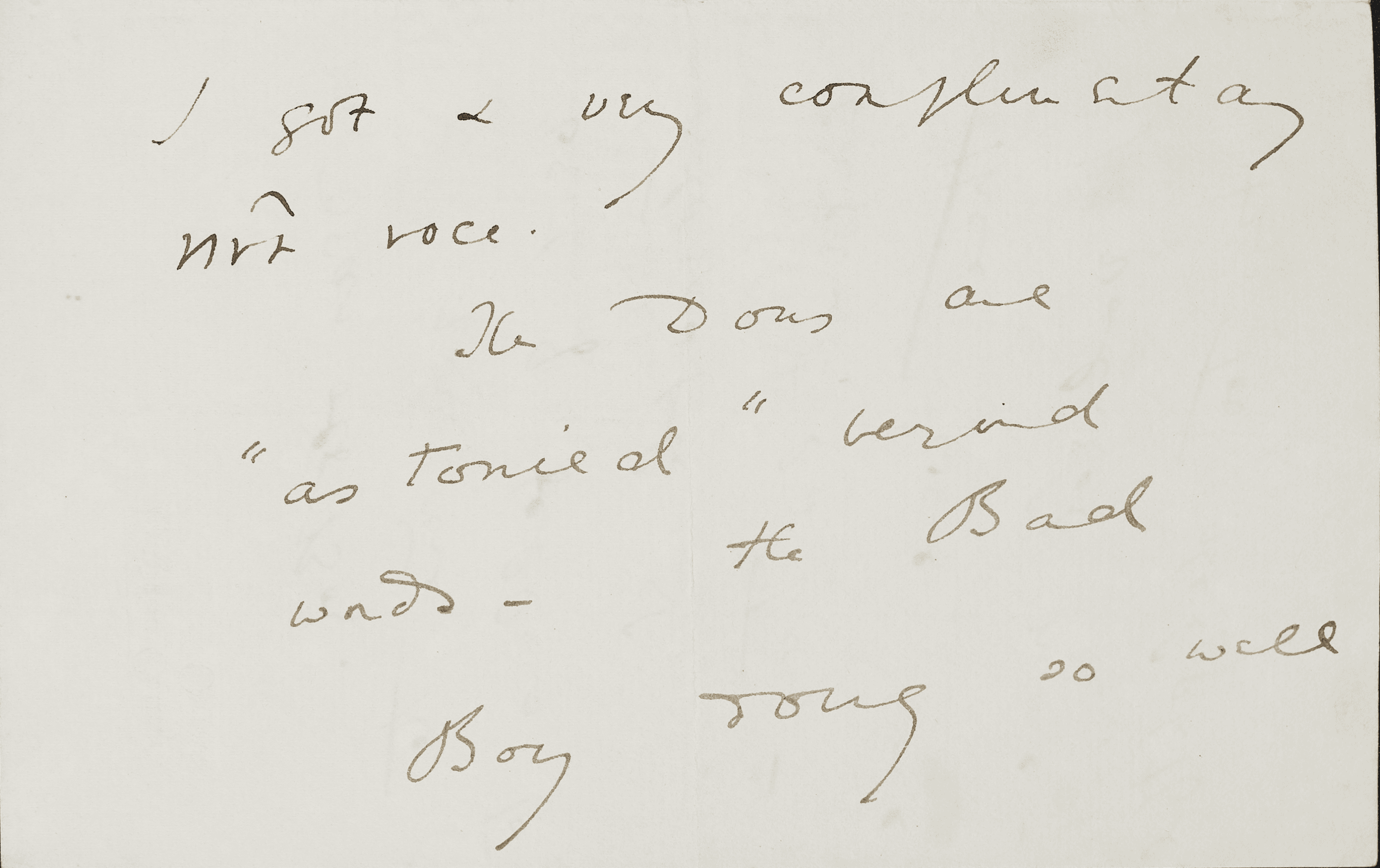

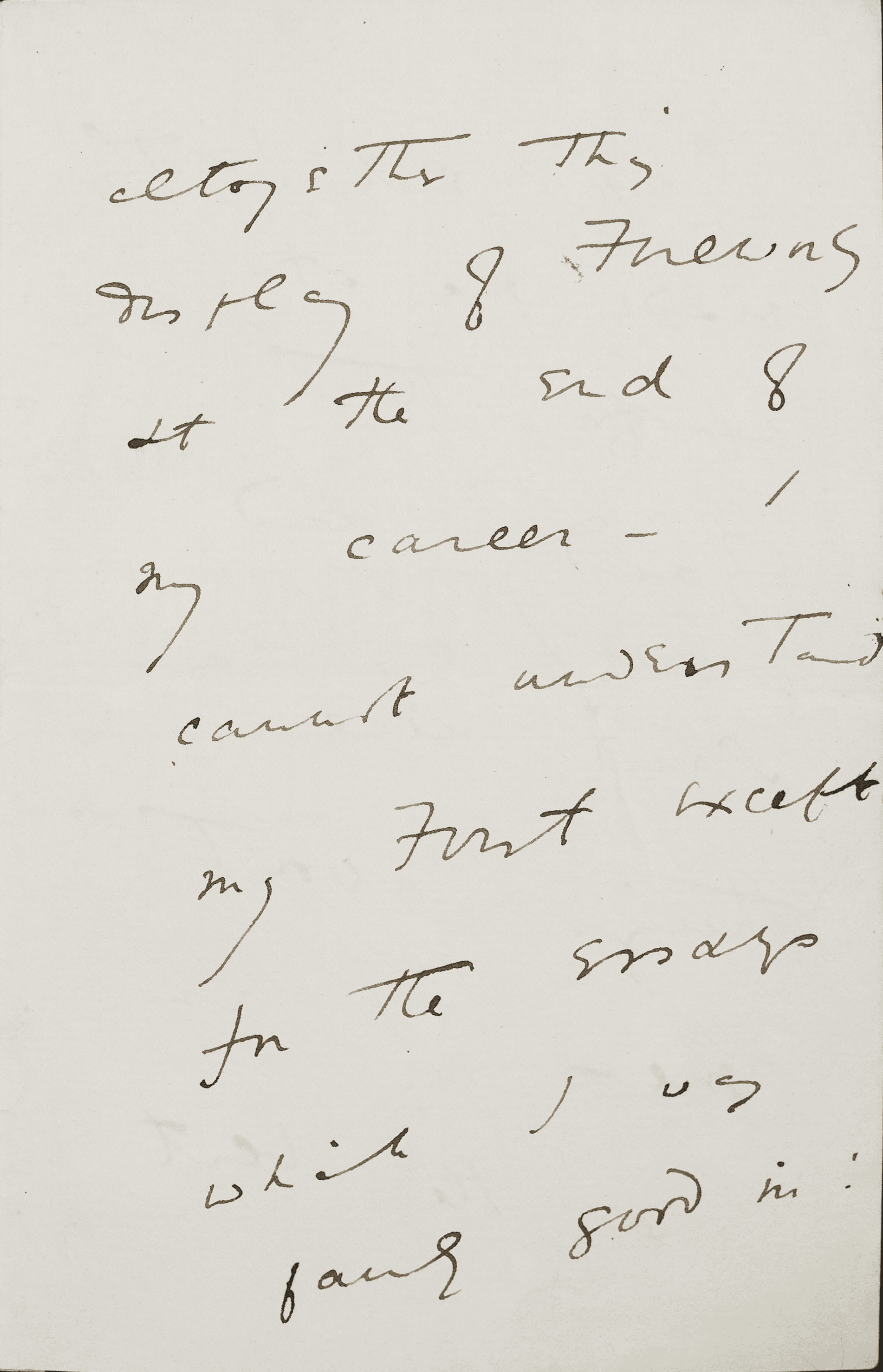

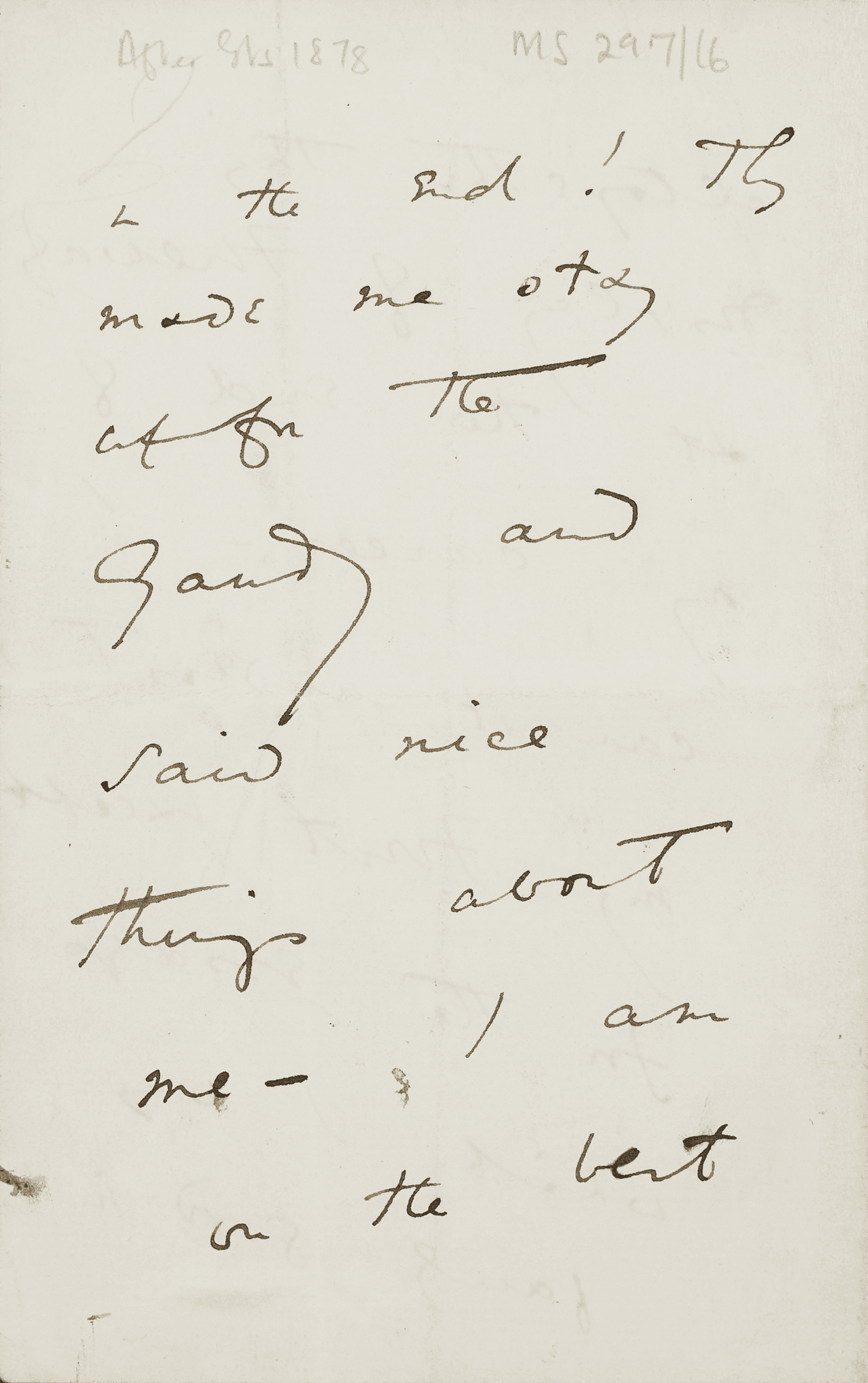

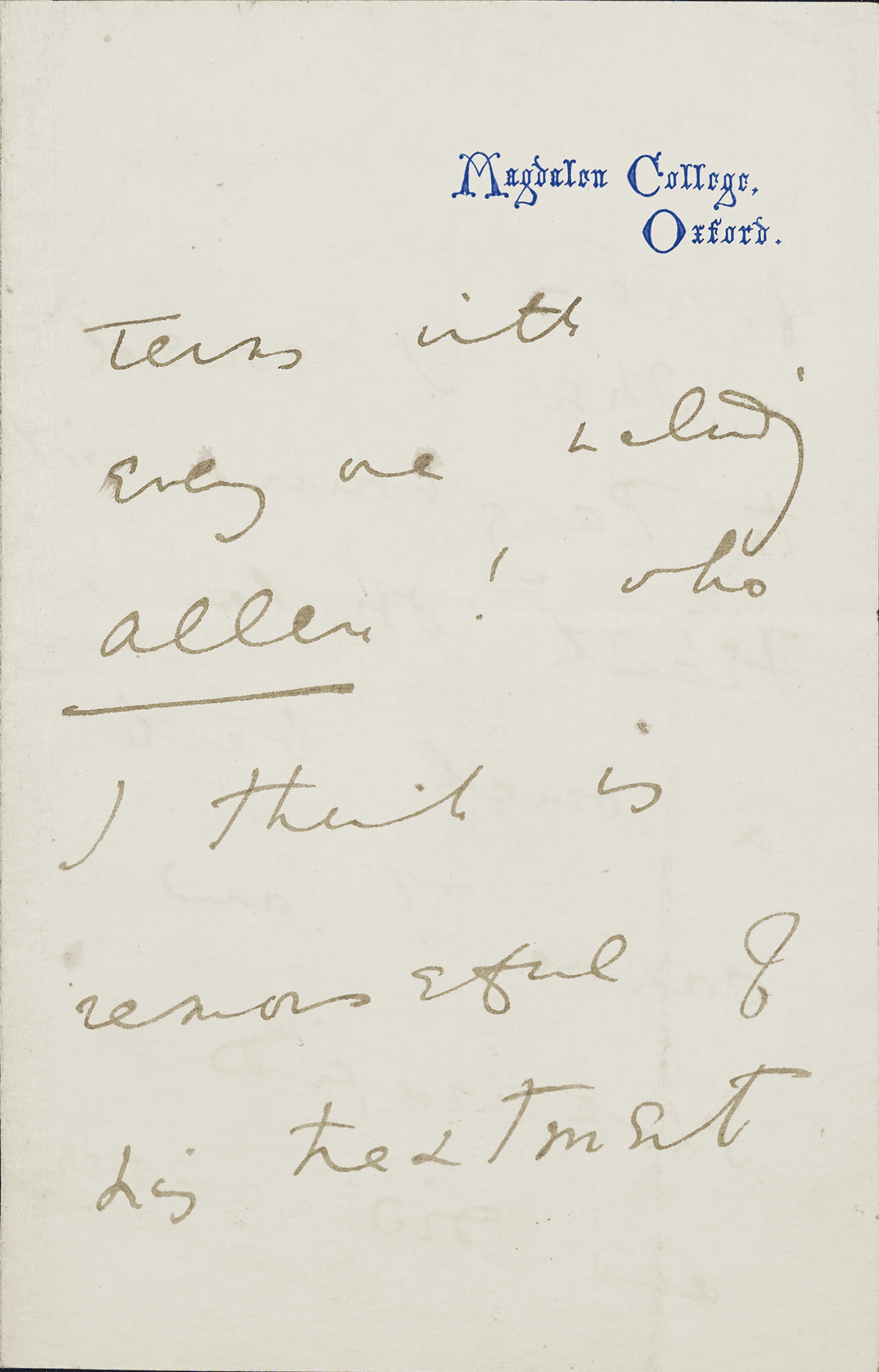

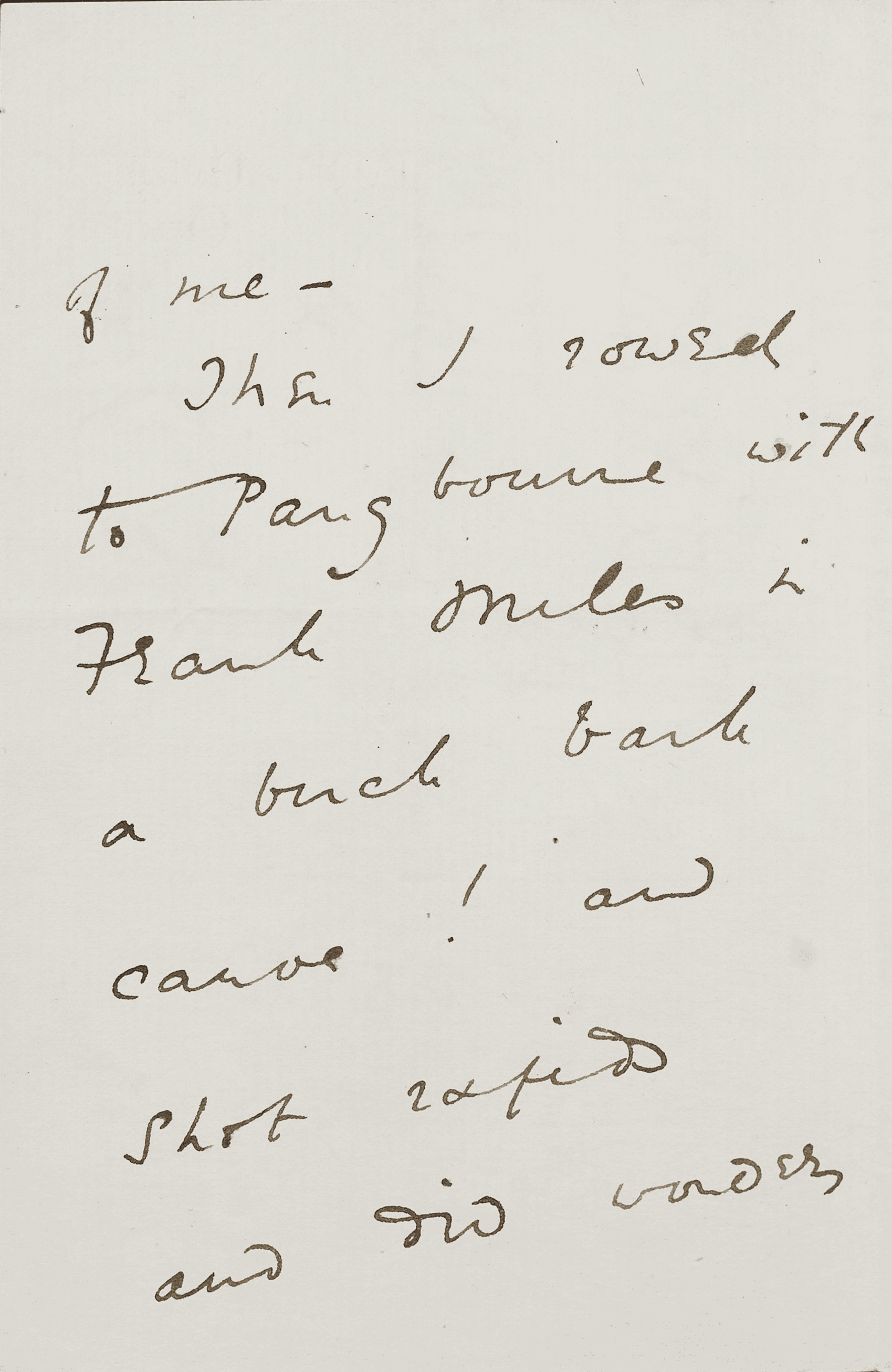

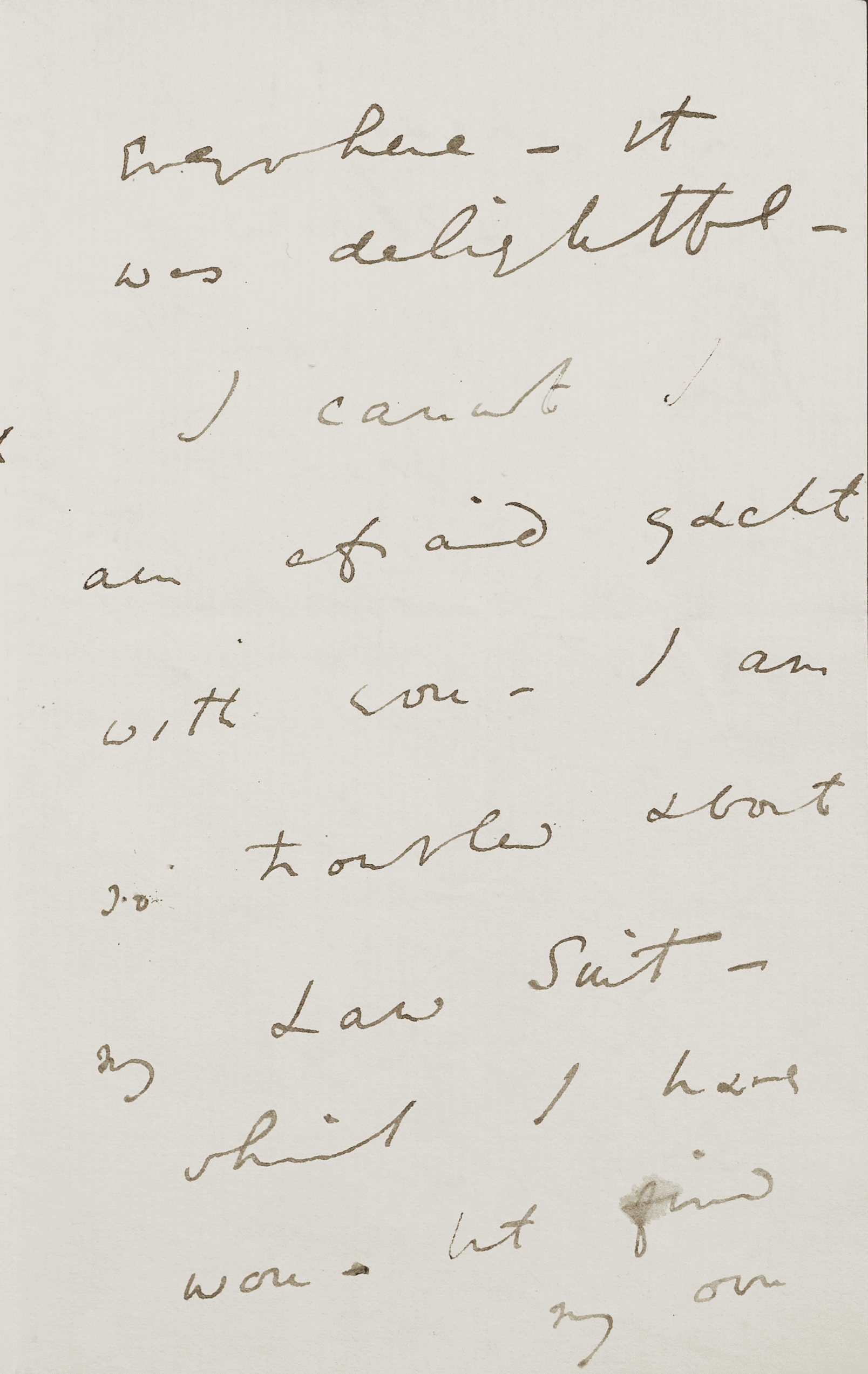

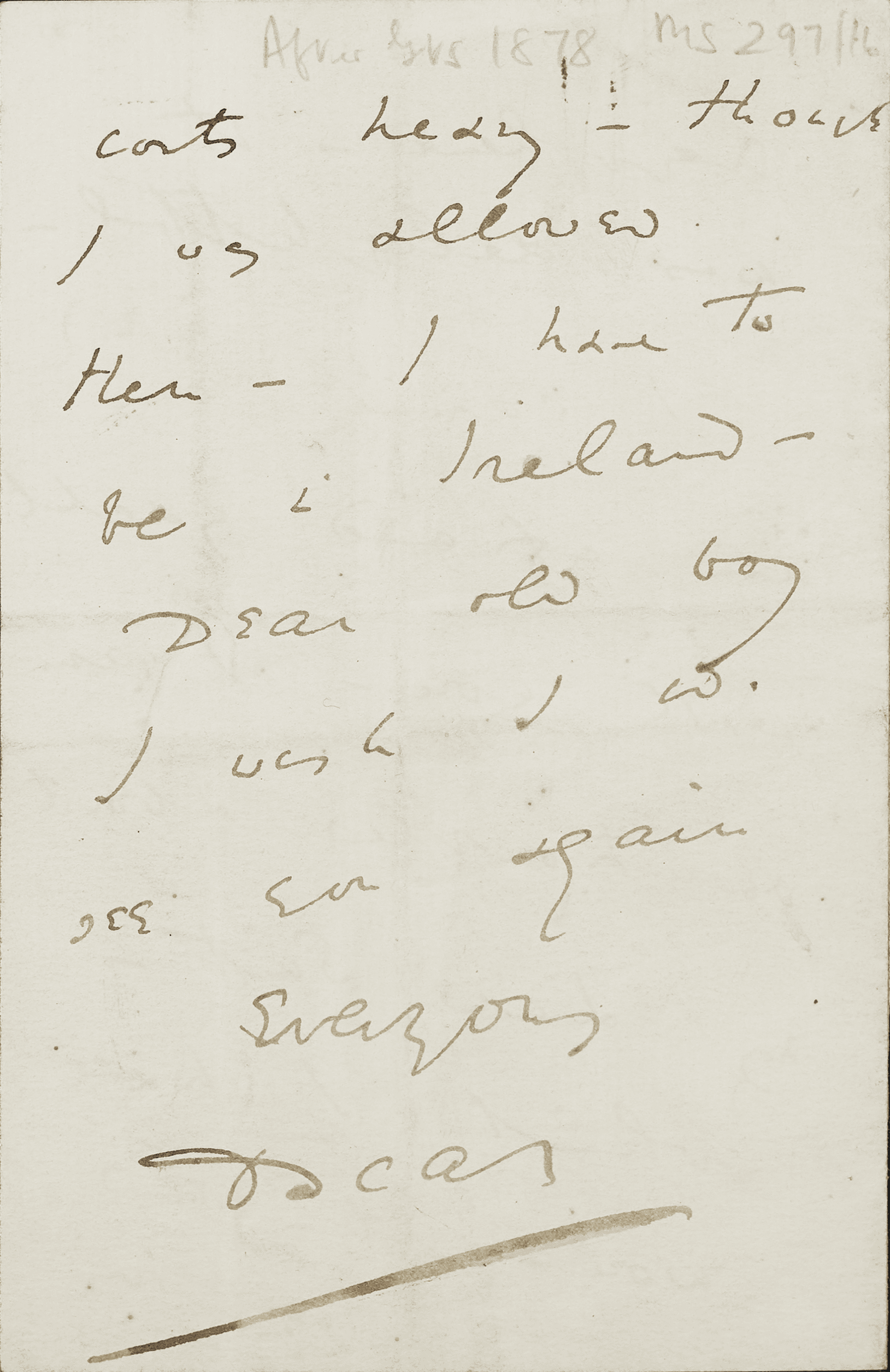

Letter from Wilde to Ward (24 July 1878)

Wilde did achieve a First in Greats; Ward wrote at once to congratulate him after reading the news in The Times. Wilde was delighted: “My Dear old Boy, You are the best of fellows to telegraph your congratulations there were none I valued more. […] The dons are ‘astonied’ beyond words – the Bad Boy doing so well in the end!”.

Magdalen College Archives, MS 297/16

The gift of Miss Cecil Ward

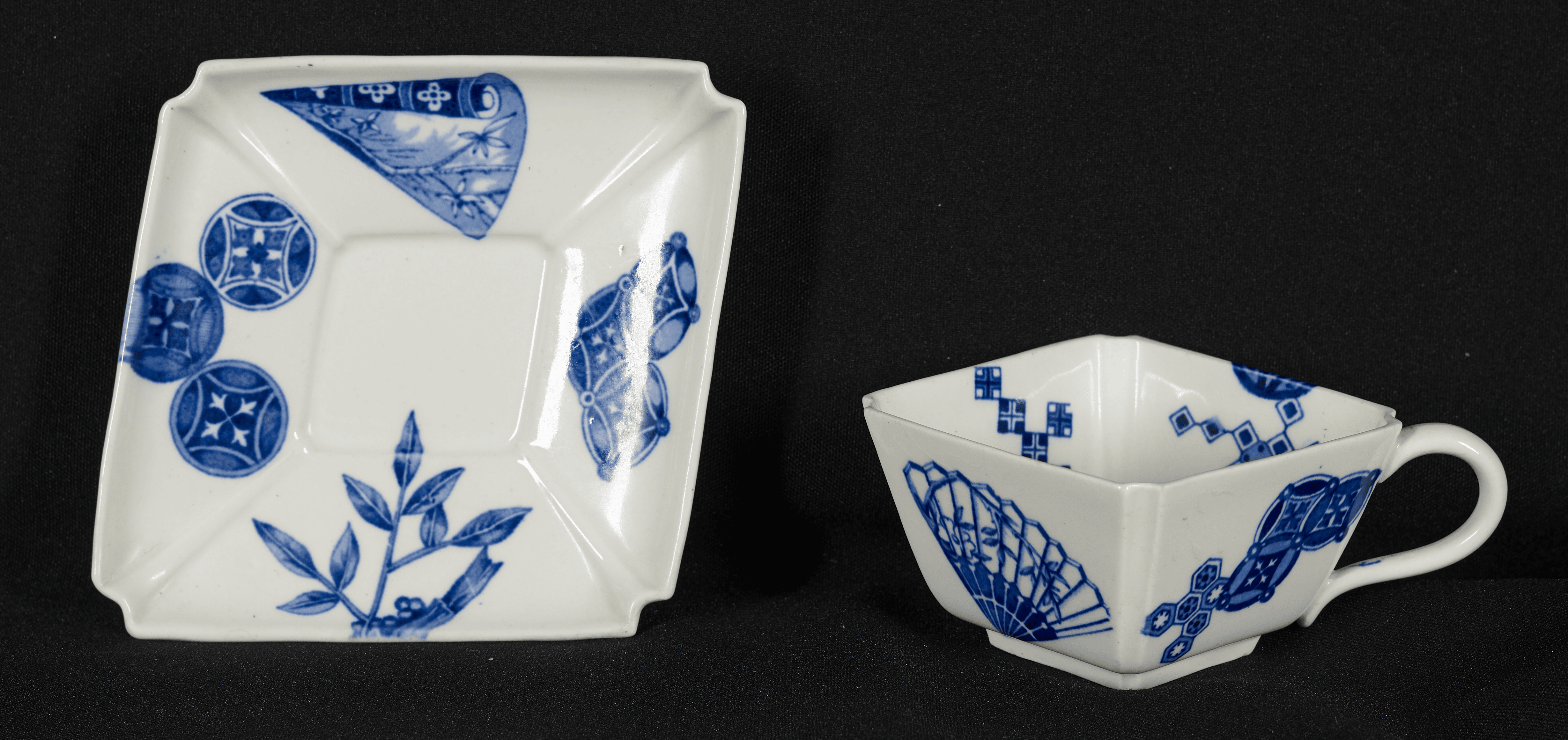

Royal Worcester Cup and Saucer (Before 1891)

Wilde’s often-quoted remark – “Every day I find it harder and harder to live up to my blue china” was made early on in his years at Magdalen, and entered the national press. By the late 1870s, “living up to blue china” was a by-word for Aesthetic inclinations – and usually the subject of merciless satire.

From the collection of Michael Seeney

Sample of “Aesthetic” Fabric (1880s)

One of many products produced in response to the Aesthetic movement; look out for the Aesthetic motifs such as eyes and sunflowers.

From the collection of Michael Seeney